One of the most characterising events of the Early Modern period in Europe were the hunts against people perceived to be witches. It is estimated that anywhere up to 100,000 witch trials may have taken place during this time, with further estimates that between half and two-thirds of these people were executed for their supposed crimes. The nature of these trials and hunts varied from country to country and century to century, but those that occurred in Trier, Germany, during the 1580s and 1590s are usually considered to be the largest of all.

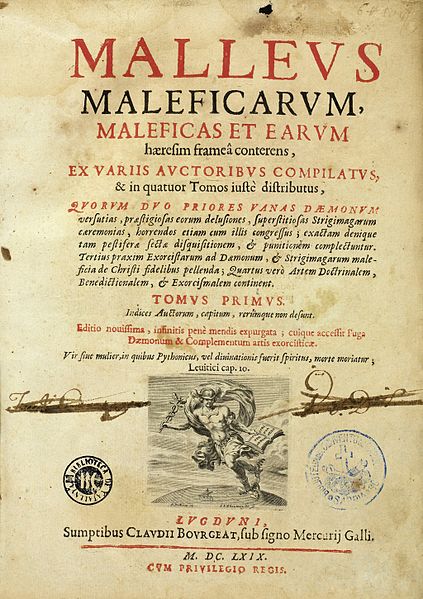

Belief in magic and witchcraft occurs in many world cultures at many different periods of time, but in Europe this belief was low during the earlier medieval period. It was only towards the end of this time – around the 14th century onwards – that belief in people capable of wielding evil magic started to rise. There were various high-profile cases of suspected witches across European courts which caused this growing belief in these evil people. In a world where Christianity and the Church held such sway, those who partook in witchcraft were seen to be heretics acting against God and in league with the devil. As the Early Modern period arrived, this belief really took a hold on the general population. Witch-hunting manuals such as the Malleus Maleficarum began to be published which narrowed down for the first time the exact characteristics of a witch, which made it easier to find these witches now that people knew what they were looking for.

Trier in modern-day Germany is a city near the country’s border with Luxembourg with a long history. Founded in the late 4th century BC, it became an important Roman settlement, eventually becoming one of the Roman Empire’s four capitals. During the medieval period, Trier was considered not just a city but a wider region controlled by an archbishop-elector under the Holy Roman Empire. This made it a particularly important region. As with many other European territories, interest in witchcraft in Germany spread towards the late medieval period. It is thought that at least 1/3rd of all those prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe came from the Holy Roman Empire, and Trier was to become one of these heartlands.

Trier was known for its association with witchcraft as early as 1484, when Pope Innocent VIII published his Bull “Summis desiderantes” which listed territories particularly troubled by witches. This was picked up by the German author of the Malleus Maleficarum, who reprinted this list alongside his editions. Throughout the sixteenth century, then, Germanic lands had plenty of time to read and hear about witches, and by the late 1500s this belief had taken a deep hold on society. Accusations of witchcraft in the Early Modern period always held greatest currency during difficult times, and it became an easy explanation for the hardships experienced by those living at that time who did not wish to blame God, nature, or themselves for these struggles. This was the situation Trier found itself at the start of the 1580s.

In 1581, a man named Johann von Schönenberg was appointed archbishop of the diocese of Trier. As a powerful Catholic ruler in charge of an important region in the Holy Roman Empire, Schönenberg decided he needed to improve the morals and calibre of his people. There had been religious wars across Europe for much of the century after the creation of dissenting Christian groups – namely Protestants – and as a man in charge of the souls of his people, Schönenberg wanted to make sure his territory was filled with good Catholics. This meant removing the three biggest groups of dissenters in society at the time: Protestants, Jews, and witches.

Schönenberg’s work was greatly helped by the timing of a series of terrible harvests in the region. Across the 18 years that he was Archbishop-Elector, a local chronicler noted that only two years had good harvests. Inexplicable crop failures and the resulting starvation, poverty and social unrest that goes alongside it was always a ripe field for doubts of witchcraft to be sown, and Schönenberg’s desire to purge unwanted people in society easily took a hold. And so he appointed one of his Auxiliary bishops, a man called Peter Binsfeld, to lead the charge.

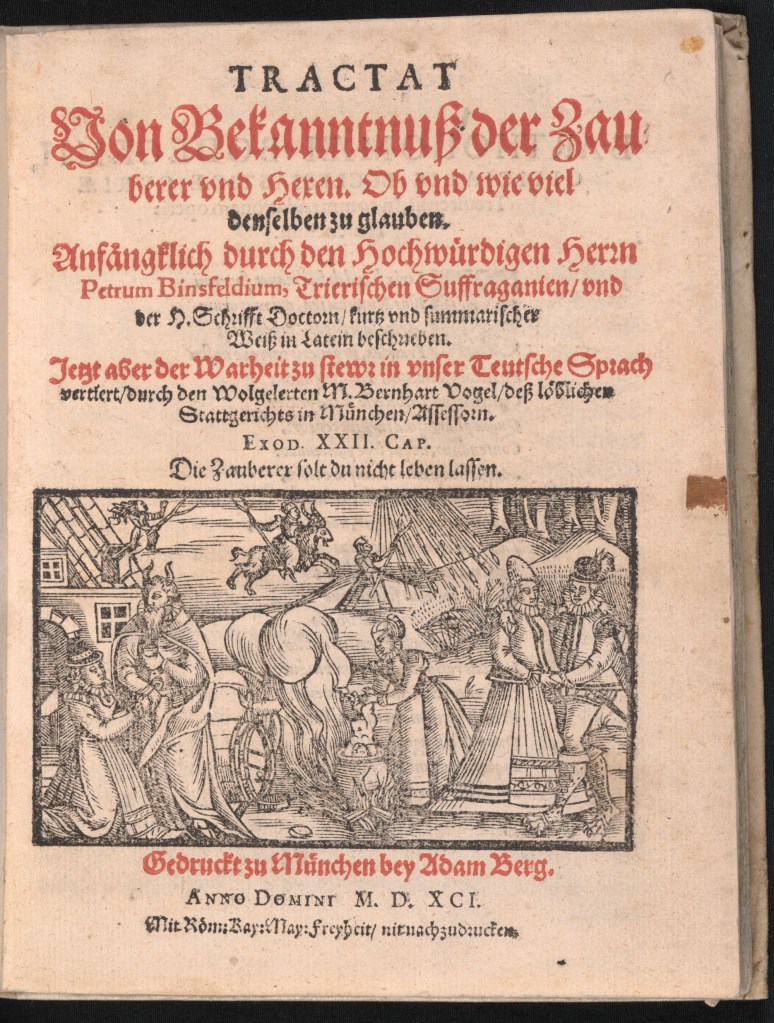

Binsfeld was a strong proponent of witchcraft. Though many in Europe at this time believed fully in the power of witches and the evil demons they collaborated with, there were others in learned circles who questioned what was becoming mainstream thought. Many had objections based on the Bible or the accepted powers of God that meant witches could not be capable of what many were claiming them to be. Binsfeld, however, accepted most aspects of witchcraft as was prevalent at that time, including the idea that witches could fly, had sex with demons, and had made pacts with the devil. Binsfeld also strongly believed that torture was necessary to extract confessions from witches because of how heinous the crime was. This belief likely contributed greatly to the numbers of persecutions which he would oversee.

Within a few years of Schönenberg becoming Archbishop-Elect, the diocese of Trier was deep in witchcraft hunting fever. Parents and children were encouraged to testify against each other, and torture was used relentlessly and mercilessly. In many areas, discontent peasants dealing with the worst of the crop failure took matters into their own hands against local officials and nobles, and a high status was not enough to protect oneself against accusations. Six years in particular, those between 1587 and 1593, were the harshest in the hunt for witches, and at least 360 people were burned alive for the crime of witchcraft. A third of these were members of the nobility and people in local government. The horror of the extent of the persecution was recorded by the tutor of the sons of the Duke of Bavaria after a visit to the region, who wrote that “everywhere around here we see almost more stakes from burned witches than green trees”.

The zealousness of Trier’s witch hunters spilled into neighbouring regions. Parts of Luxembourg that came under the diocese of Trier found far higher rates of execution of witches than their Francophone counterparts at this same time. Neighbouring territories who wanted to start trials of their own often cited the prevalence of witches in Trier as a reason to begin their own hunts.

Despite all this, there was some resistance to the hunts spearheaded by Binsfeld. The chief judge of the electoral court, and the rector of Trier University, was a man named Dietrich Flade. Due to his position, Flade had been called upon to preside over some of the witch trials for the region. Flade was not as vehement in his belief of witchcraft as some of his colleagues, and he did not approve of the use of torture against the alleged witches. The cases he was involved in were noted for his more lenient treatment of the accused, and this brought suspicion upon him by the witch hunters. In 1587, several accused witches began to implicate Flade in their confessions, alleging that they had seen him attend sabbats (gatherings of witches often with demons or the devil). These confessions may well have been encouraged by their torturers, keen to gain any ammunition against him. Whilst Flade petitioned to clear his name, more and more accusations came in, including ones accusing him of destroying local crops and engaging in cannibalism. Flade was finally arrested in 1589, his trial taking place a few months later. He attempted to defend himself, but succumbed to torture and confessed to his supposed crimes. He suffered the same fate as so many in the region, and was executed for his witchcraft, one of the most prominent executions of the trials.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Flade was not the only person to question the validity of the Trier witch trials. Another of his university colleagues, Cornelius Loos, was a Catholic priest and theologian. Having observed the trials – including that against Flade – Loos took time to study his beliefs and that of his religion, and decided what he knew and believed did not match with what was taking place. Loos argued that demons were pure spirits that cannot take on physical forms, and so they cannot affect tangible reality – therefore any confessions of witches only proved delusions from the confessor, or were the result of excessively harsh torture. Loos’ ideas were not necessarily radical, and indeed countries that did not employ torture often saw lower rates of witchcraft confessions and convictions. But Loos decided he wanted to publish his thoughts, and that was not in the interests of the witch hunters who had been profiting greatly from the trials of the previous few years.

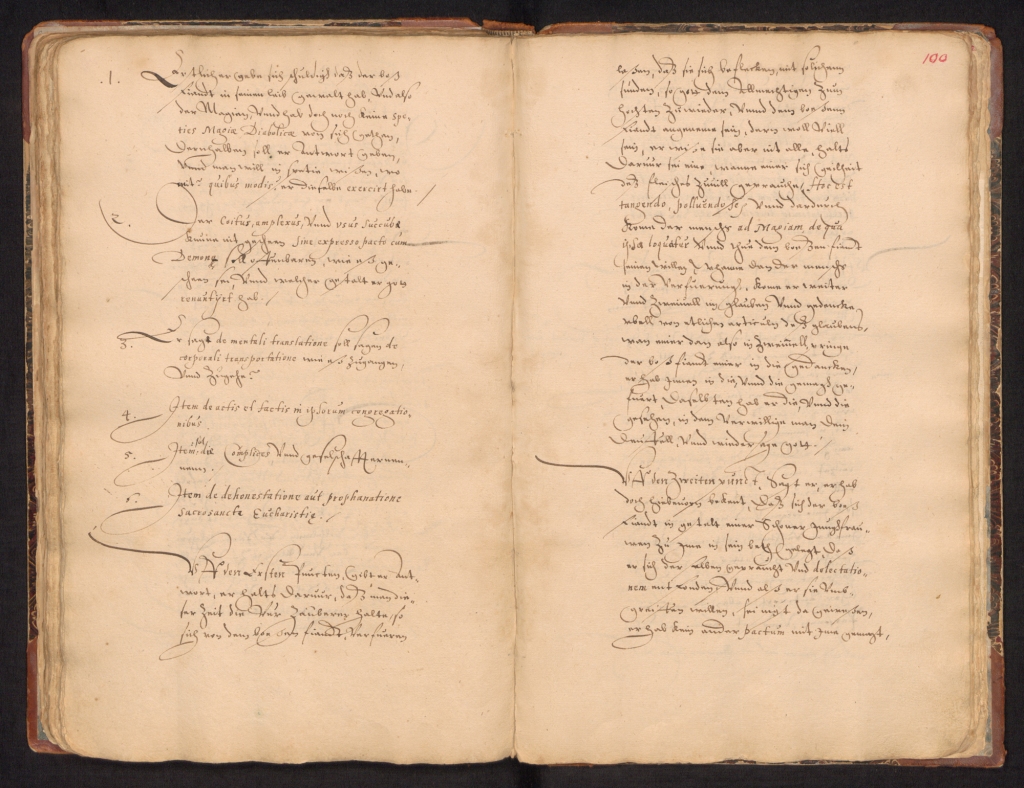

The manuscript that Loos wanted to publish was confiscated, and Loos was arrested. His ideas were dangerous, but perhaps because of his position, officials were loathe to execute him too. Instead, he was forced to undertake a public recanting of his beliefs in front of church officials in 1593. From that time onwards he was put under constant surveillance, and was imprisoned several more times, though released each time. He died 2 years later from the Plague.

With questions starting to circulate about their methods, and particularly after the high-profile execution of Flade, Binsfeld was under pressure to defend himself. In 1589, the year of Flade’s execution, he printed at Trier in both Latin and German his “Treatise on the Confessions of Witches and Sorcerers” justifying his ideas and actions. This was published once again two years later. Despite this, by the year of Loos’ recantation, much of the steam of the past six years of persecution had blown away. Accusations of witchcraft by no means disappeared, and the region was still plagued by intermittent trials for decades to come. But the main days of the Trier witch hunts were over.

Binsfeld and his team had certainly been busy. Surviving records show in glaring detail the full horror of what took part in Trier. One official, named Claudius Musiel, had a register of suspects made for him which lists over 6,000 accusations from over 300 executions in the region over just a few years. Over 100 trial dossiers survive from this time which include many names not found in Musiel’s register. This alone leads historians to suspect that the surviving material does not cover the entirety of the persecutions, and that the death count was even higher than the more than 300 we know took place in the city. Estimates by historians place the total killed for being suspected witches at between 500 to 1000 people across the mid-1580s to the early 1590s in the diocese of Trier. This makes it not only likely the largest documented witch trial in history, but also perhaps the largest mass execution in Europe in peacetime.

The witch hunts that came out of Trier in the late sixteenth-century were by no means unique across Early Modern Europe, but they were certainly notable for their ferocity and their extensiveness. Hundreds of men, women, and children were burnt at the stake for their alleged confessions of witchcraft, many of whom after having been horribly tortured. Families were encouraged to turn on each other, and the accusations cut across social class. Those who attempted to question the rationale of the hunters found themselves hunted, and thus dissent was crushed by those who gained huge material wealth and status from being the persecutors. The events in Trier were certainly a dark time in our human history.

Did you know that Just History Posts now has a newsletter? Be sure to sign up here!

Previous Blog Post: Historical Objects: The Bees of Childeric I

Previous in Witchcraft: Did Gertrude Courtenay accuse Anne Boleyn of witchcraft?

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

The German Witch Trials | The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

“Let No One Accuse Us of Negligence” The Influence of the Witch Hunts in Swabian Austria and the Electorate of Trier on Other Territories from “Evil People”: A Comparative Study of Witch Hunts in Swabian Austria and the Electorate of Trier on JSTOR

Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, Volume 4 – Google Books

bodin (hanover.edu)

Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia – William E. Burns – Google Books

One response to “Trier: The World’s Worst Witch Hunts?”

[…] Previous Blog Post: Trier: The World’s Worst Witch Hunts? […]

LikeLike