Objects made in previous centuries hold great power over us today. Whether it is admiring the stunning craftsmanship of people who lived long ago in much harsher times but still wanted to create something beautiful, or forging a connection between people whose lives were so different to our own and yet used the same everyday items as us, historical objects constantly capture our imagination. It’s why we have museums full of items the world over. One favourite of mine is two little golden bees. Over 1,500 years old, these bees appear unassuming, and yet their history provides a compelling and dramatic story. So, what are Childeric I’s bees?

Today the world is full of professional archaeologists undertaking excavations. There are also plenty of stories of amateur metal detectorists or ordinary members of the public coming across amazing historical artefacts. In many ways, we consider this interest in the past a modern phenomenon. People today get excited about unearthing objects from the 17th century, but our story in fact starts in this century, and people were just as excited back then…

The 27th May 1653 likely started as any other for mason Adrien Quinquin. A man working on a construction site in Tournai, modern-day Belgium, he was several feet under the ground swinging his pickaxe when he hit something unusual. A glint of gold shimmered up at him. After gathering the attention of nearby people, the rest of Quinquin’s hole was dug up. Inside was a real treasure trove: human bones, hundreds of silver coins, a highly decorated sword and scabbard, and many more gold items including buckles, rings and brooches. Key for us, there were also 300 little bees made from gold. The excitement was palpable.

News of such an amazing find quickly spread to the highest levels; soon Archduke Leopold William, who was Governor of the then Spanish-ruled region, caught word of the treasure and he wanted it. No one could say no to the brother of the Holy Roman Emperor, and so the hoard was sent to the Archduke in Brussels. Now, Leopold was a refined man who was a renowned patron of the arts. He didn’t just want the treasure as a status symbol – he was genuinely fascinated by the find. And so he recruited an unusual ally: his physician.

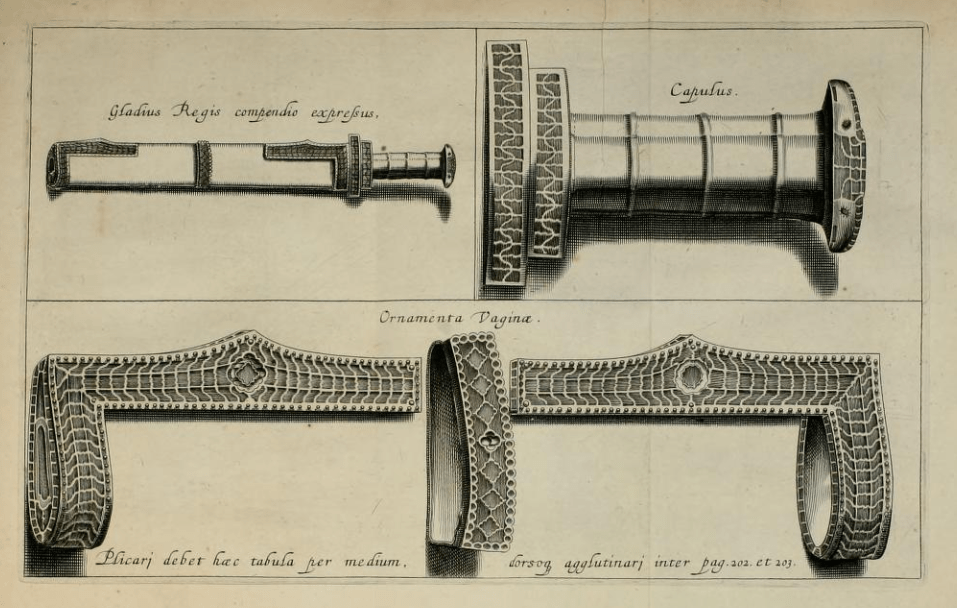

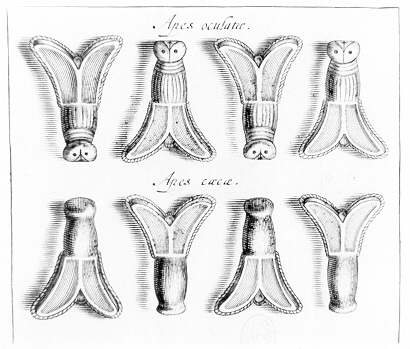

Whilst a medical doctor may not seem like the standard choice, Jean-Jacques Chifflet was also a historian. Leopold had him study the find intently, and Chifflet delivered. A few years later, in 1655, Anastasis Childerici I. Francorvm Regis, sive Thesavrvs Sepvlchralis Tornaci Neruiorum … (The Resurrection of Childeric the First, King of the Franks, or the Funerary Treasure of Tournai of the Nervians) was published detailing his results. Chifflet had been meticulous in his research, and the resulting book was over 360 pages long and had 27 plates of engravings of the artefacts. Whilst Chifflet did take some artistic licence in embellishing the drawings, they were largely accurate and pretty detailed.

Chifflet took pains to identify the items from the hoard, and he also managed to identify the owner of the objects: a 5th-century Frankish king called Childeric I. Whilst Chifflet did end up misidentifying some of the pieces, his approach in his research and recording the outcomes is now often considered the first scientific archaeological publication. The key to identifying Childeric came from a ring which had a depiction of a long-haired, clean-shaven man holding a spear and wearing Roman-style clothes. Around the edge of the portrait were the words “Childirici Regis”. This made the find even more exciting, as Chifflet identified this Childeric as the father of King Clovis I, the first ruler to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one leader and thus considered the creator of the French monarchy.

Childeric I had died in 481 AD, making this a very old find even back in the 17th century. He ruled at a time when the influence of the Roman Empire was waning and new dynasties were springing up. The image of Rome was still powerful enough for Childeric to want to be portrayed wearing Roman clothing on the ring, but new traditions and cultures were starting to emerge and this mix was reflected in the items buried with the king.

Leopold treasured the collection until his death in 1662, upon which it was bequeathed to his nephew, another Leopold. This Leopold was Leopold I, King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia, and he had become Holy Roman Emperor after the death of his father. He prized his uncle’s collection and had replicas made of the items in Childeric’s hoard. Despite his care for the collection, sometimes politics came above the arts, and in 1664 Leopold had been in a difficult spot. The Ottoman Empire were encroaching on his Hungarian kingdom, and King Louis XIV of France had provided military aid to repel the invaders. To show his gratitude, in 1665 Leopold gifted the Childeric hoard to the French king, believing it a grand gesture to return it to Childeric’s descendent.

The saying goes that one man’s treasure is another man’s trash, and the hoard was certainly an exemplifier of this. The Sun King, who was bathed in luxury, did not consider these measly golden scraps from over 1,000 years prior to be very much of anything, and stored the hoard away in his Louvre palace. This decision of Louis’ may well have helped save the collection from later political turmoil. After the French Revolution, when many items related to the monarchy were destroyed, Childeric’s Hoard was kept alongside the objects it was stored with to form a collection within the Imperial Library, which later became the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Whilst King Louis had not appreciated the value of the hoard, a subsequent French leader was to define himself by it. In 1804, a man named Napoleon Bonaparte declared himself Emperor of France. Two years prior, the country had voted to make his government permanent, but Napoleon needed a way to justify his new grandeur and position in a way that distanced his rule from the divinely-ordained monarchy he had helped to overthrow. One way Napoleon and his advisors attempted to reconcile this was by using imagery that linked them to the Ancient Romans, those beacons of democracy and power. But every regime by this time needed a symbol, so what should represent this great Emperor?

Much debate circled behind government doors about which animal could best represent the splendour of France. But no one could quite agree on what was best. Eventually, Napoleon decided that an Eagle should be the heraldic animal of the regime. But what about an emblem? The classically French fleur-de-lis held too many connotations of monarchy. Then one consul, a lawyer named Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès, suggested a curious item: the little golden bees found in the hoard of Childeric I. The bees seemed a perfect solution. The shape bore a resemblance to the fleur-de-lis (indeed, Chifflet had suggested in his monograph that the bees may have been the originator of the fleur) whilst connecting to the earliest days of France as a country, and a time where Imperial Rome still held sway.

From this time, the bee became not only the emblem of the French Empire, but the personal representation of Napoleon himself. His coronation robes were scattered with gilt wire bees, and they also appeared on the robes and slippers of his wife’s coronation outfit. Napoleon’s imperial homes were all covered in the emblem, and they could be found on carpets, wall-hangings, furniture, ceramics and glasses. His cloak which was captured during the Battle of Waterloo even had a clasp with two bees. Almost 1,400 years after the golden bees had adorned the funeral cloak of Childeric, it was once again representing his kingdom.

Throughout these tumultuous years, Childeric’s hoard had stayed safe and sound at the Bibliothèque nationale. But on one fateful night – 5th November 1831 – that was to change. A group of thieves broke in to the library and stole over 2,000 golden treasures from within, including the entirety of Childeric’s hoard. Although a huge police manhunt was launched and a group of suspects were arrested, much of the treasures had been lost forever. The thieves eventually revealed that they had melted down most of the golden treasure into ingots for easier use, and the pieces that were heavily laden with jewels (like the bees) were thrown into the River Seine. The police recovered 20 ingots of gold from the thieves’ hideout, and following information from the confessions, managed to dredge the river where the items had been dumped and found 8 bags filled with 1,500 of the stolen items. When the weight of the recovered bags and the ingots were combined, it was judged that the entirety of the stolen treasure had been located.

Coronation portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte from the Workshop of François Gérard, with details showing bees on Napoleon’s robes and the carpet. WikiCommons.

Although so many items had been recovered intact, unfortunately Childeric’s treasure had been severely impacted. Almost the entire hoard was lost, with just 2 coins, 2 bees, and the fittings from Childeric’s sword and seax being found. Only Leopold’s reproductions and the drawings by Chifflet remained to show what had once been. The items were returned to the Bibliothèque nationale, where the two little bees remain today.

And yet, the story of these little bees was still not over. In the 1980s, excavations were undertaken by a man named Raymond Brulet in Tournai. Extensive research was being done on the town which had risen to great heights towards the end of the Roman Empire. Brulet was trying to learn more about Childeric’s burial and to place it in context with the wider area at his time. Because of Chifflet’s exemplary report the exact location of the discovery was known, but access was not possible because a house with a deep cellar had been placed on the site. However, Brulet obtained permission to dig up the street in front of it as well as the back garden.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Brulet’s excavations revealed something previously unknown. Childeric’s grave was not a lone monument in an obscure location, but was in the midst of a significant cemetery of the period. His burial there may even have served as a focal point that created the cemetery as others wanted to be buried by this great king. This dig also showed just how significant Childeric’s burial had been. Beyond the luxury of the items buried with the king, the archaeologists discovered three pits filled with dead warhorses around the tomb, as well as evidence that Childeric had been buried in a huge grave mound 20 metres in diameter. It would have been clearly visible from the nearby Roman road, and likely would have been visible from far outside the town.

Front and back view of one of the golden bees, showing how it was attached to Childeric’s cloak. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

350 years ago, an amazing treasure was found in a small city. Despite the grandeur of the contents, it was a collection of tiny gold bees which made history. Though just two remain today, they tell a tale of the fall of a great empire, the rise of a new dynasty, the slow change of culture, the way powerful people will appropriate history for their own uses, and of human greed. These beautiful bees have seen plenty of history and been part of it themselves, and I think they are absolutely wonderful.

Did you know that Just History Posts now has a newsletter? Be sure to sign up here!

Previous Blog Post: Royal People: Mansa Musa, The World’s Richest Man?

Previous in Historical Objects: Seeing the Dead: The Fayum Mummy Portraits

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

Tomb of Childeric | Encyclopedia.com

Childeric I | Early Medieval Archaeology (archeurope.com)

Napoleon and the Bees: How 5th Century Jewelry From the Tomb of Childeric I Became a Symbol of Empire — Heart of Hearts Jewels (hhantiquejewelry.com)

The great find and great loss of Childeric’s treasure – The History Blog

Merovingian Bees. | Library of Congress (loc.gov)

Anastasis Childerici I. Francorum regis, siue, Thesaurus sepulchralis Tornaci Neruiorum effossus, & commentario illustratus : Chifflet, Jean-Jacques, 1588-1660 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Archeurope: Early Medieval Archaeology – Childeric – Chifflet’s Publication

6 responses to “Historical Objects: The Bees of Childeric I”

[…] • The Bees of Childiric, explained. […]

LikeLike

[…] Previous Blog Post: Historical Objects: The Bees of Childeric I […]

LikeLike

[…] More on bees: check out these cool gold ones; a handcrafted website with everything you’d ever wanted to know about beekeeping; why can’t we […]

LikeLike

[…] And that bee? The original Childeric, a Merovingian king, has a particularly famous set of grave goods. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Previous in Historical Objects: The Bees of Childeric I […]

LikeLike

[…] Historical Objects: The Bees of Childeric I Objects made in previous centuries hold great power over us today. Whether it is admiring the stunning craftsmanship of people who lived long ago in much harsher times but still wanted to create something beautiful, or forging a connection between people whose lives were so different to our own and yet used the same everyday… […]

LikeLike