Today we have a really interesting guest post lined up for you. I’m happy to introduce Catherine Williams, a graduate student in Early Modern Studies, who will be telling us all about White women in the Early Modern American South. These women held unique positions of power and authority through their scarcity and through the slaves that they owned and managed. Over to you, Catherine!

Allow me to set the scene with the story of Elizabeth Taylor, not the actress but a 1773 bride-to-be from the Early American South. Elizabeth and her fiancé Philip Johnson were not the main characters. Her mother, Ann Taylor, played the leading role. By the 1770s, it had become tradition in the Early American South for mothers to intervene with their daughter’s dowries. Including slaves in their daughter’s dowries was not uncommon in the Early American South either. Mothers recognized a slave’s value to their engaged daughters. They were keenly aware of the position of authority that came with owning slaves. Even thinking a few steps ahead, Ann Taylor included a clause concerning the slaves’ children. Assuming the slaves would reproduce, Ann Taylor secured inter-generational property ownership and authority for her daughter Elizabeth.

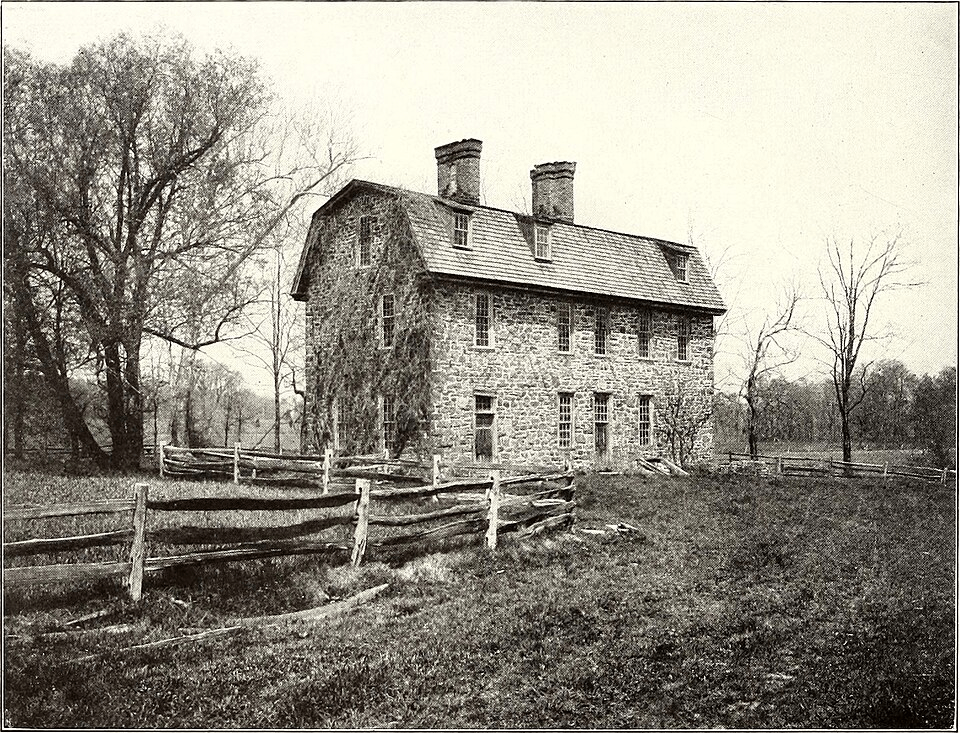

The story of Elizabeth and Ann Taylor opens a window into the Early American South. Landed women exercised authority on a plantation both within and beyond traditional gender roles. Ann Taylor exemplified several Early American Southern women in identical positions. As a mother, Ann Taylor sought favourable terms for her daughter’s dowry. But beyond this, including slaves in a dowry was a business decision that affected the plantation’s operations. To heavily invest in the dowry, Ann Taylor likely hired an overseer to, simply put, do all her dirty work. Standardized clauses, and some fairness towards the groom-to-be, attested to stabilized demographics. Hiring overseers was a solution to a landed woman’s internal value conflict between domesticity and dominance. Throughout the Early American South, White landed women occupied positions of authority, leading the domestic economy and filling commercial roles on plantations.

White Early American Southern Women faced an internal conflict between domesticity and dominance on plantations. Their primary obligation was to be ornaments of the family. It meant that these women were to be as perfect as humanly possible to positively represent their families. In historical reality, just simply being an ornament was not possible. Landed women found themselves in positions of authority on plantations that fundamentally clashed with their family ornament duties. It was simply unavoidable. Hiring overseers was one solution that resolved a landed Southern woman’s internal value conflict between domesticity and dominance. They paid someone else to supervise slaves and run plantation(s). Absenteeism created the opportunity for women to live outside their plantations across the Early American south. However, overseers could not be trusted. Female plantation owners often accused their overseers of mismanaging their plantations. A general mistrust in overseers made it impossible for these women to solely pursue domesticity. They had to intervene in plantation affairs at some point.

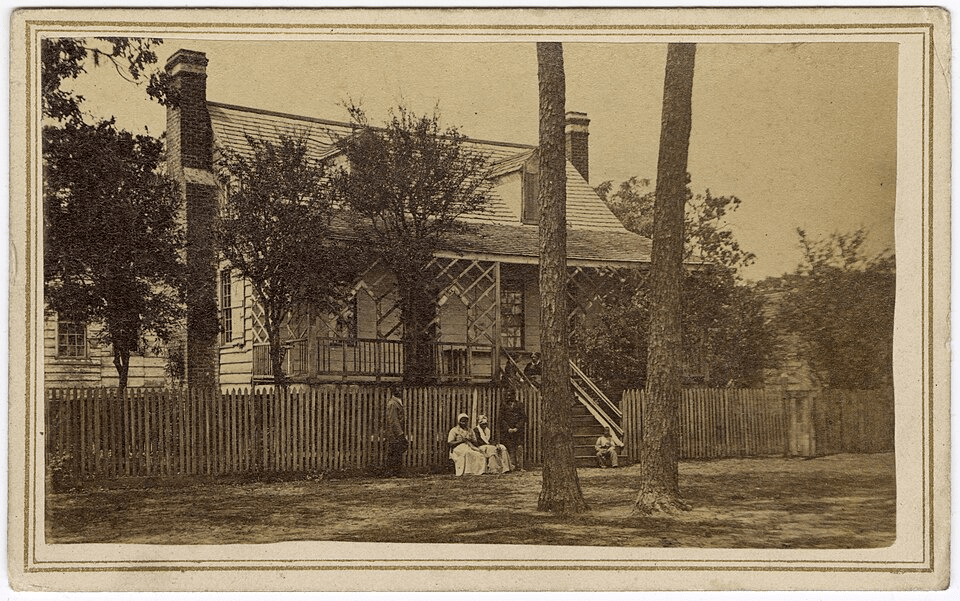

It was quite common for White women to assume leadership roles in the plantation’s domestic economy. With the assistance of accounting manuals, it was easier for her to manage household expenses that were separate from the plantation economy. They were advised to allocate money to pay wages of housekeepers and servants. While they supervised wage laborers, they also closely managed unfree domestic slaves. Domestic slaves were almost always women because they could assume childcare responsibilities. Mistresses assigned menial household chores, like cooking and cleaning, to domestic slaves. If a domestic slave was not assigned to complete household chores, she could have been a mistress’ personal servant, tasked with looking after her clothing and appearance. Yet, mistresses shifted their own child-rearing responsibilities to a domestic slave whose sole purpose was caring for White children. Landed parents had oversight in their children’s upbringings while the day-to-day matters fell on female domestic slaves. Freedom from their own children allowed a woman’s authority to expand beyond domestic spaces. In subordinating others, White Early American women occupied and asserted positions of authority on plantations.

Before we continue, it is important to ask the question of how could these women get away with everything? Paying overseers and subordinating poor white men, distancing themselves from their children at the expense of an enslaved women’s kinship, dealing in slaves, the list goes on. The answer is simple: commodification. White landed women were commodities in the Early American South. In the seventeenth century, as was the case with many fledgling colonies, there was a demographic imbalance. With more men than women, and particularly few landed women, white landed women were commodities. These demographics stabilized in the eighteenth century, it only took about 100 years or so. Yet White landed women remained commodified because marriage was just that important. White landed women could be more selective with marriage offers, and exercised authority in choosing to whether to accept or reject a marriage offer. Landed men benefitted too from being married to landed women in the Early American South. But marriages were short, and remarriage was a woman’s golden ticket. Including slaves in a dowry was particularly advantageous because it guaranteed a pathway to occupying and asserting positions of authority on a plantation.

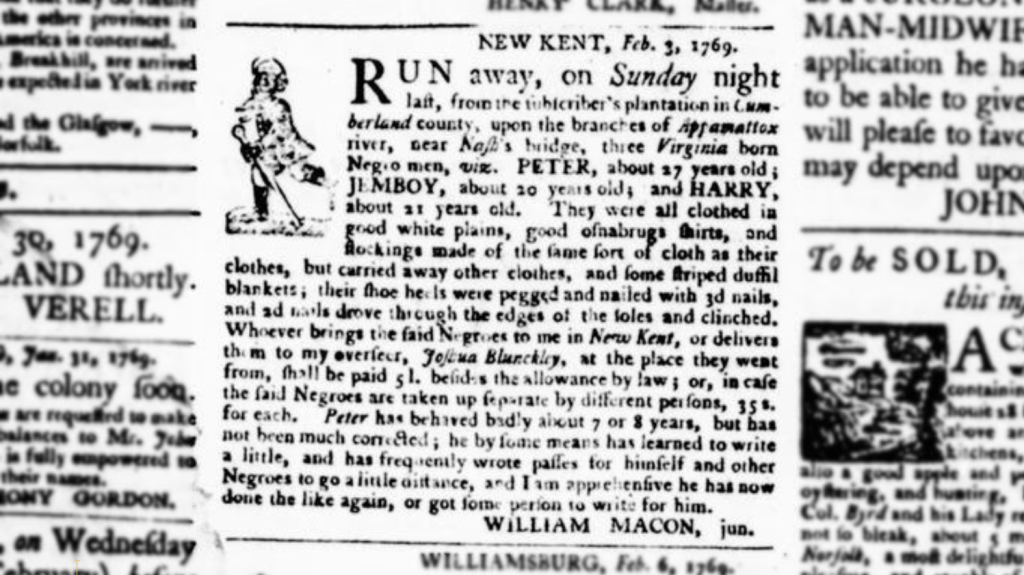

Being a delegator, which involved assigning others to complete tasks on behalf of the plantation owner, prepared unmarried women for a career in plantations. It was a woman’s first taste of plantation authority. Delegates commonly placed runaway slave advertisements. These advertisements worked to subordinate multiple people simultaneously. Inherently, a runaway slave who got caught was denied freedom and punished upon their return. Slave catchers were not landed men. They were plebian or poor White men lured with a reward to find and return a landed person’s property. Not every advertisement promised a worthwhile reward for a task that could take months to complete. A runaway slave’s return (or the slave catcher’s reward) was not guaranteed. Ultimately, a landed woman occupied a position of authority as a delegator and asserted it with runaway slave advertisements. Poor men followed a wealthy woman’s instructions to return property.

Joint-mastery partnerships gave married women the opportunity to equally operate a plantation alongside her husband. Joint-mastery partnerships were common enough in the Early American South for the law to catch up. Husbands and wives could be accused of impropriety towards their slaves. Therefore, wives in joint-mastery partnerships brought moral imperatives to their business relationships to avoid such accusations. Wives in joint-mastery partnerships continued placing runaway slave advertisements. These landed wives generally offered higher rewards than advertisements placed by landed men. If a runaway slave was found, the wife would pay the slave catcher and personally collect a runaway slave from the local jail. Equality lied at the heart of all joint-mastery partnerships, which prohibited joint-mastery husbands from subordinating their wives. Being a joint-mastery wife gave Early American Southern White women the same degree of authority on a plantation as their husband, and they asserted it with each business dealing.

Early American Southern women owned entire plantations and the slaves who labored on these plantations, but there were more opportunities for women to acquire slaves than plantations. Slaves were birthday presents, holiday gifts, and integral to a landed woman’s marriage agreement. With each slave came the intangible position of authority as a slave owner. Plantations, however, were usually inherited from their late husbands as outlined in his will. Each marriage presented women with the opportunity to inherit additional plantations from successive dead husbands. Women who inherited plantations inherited the corresponding position of authority as a plantation owner. Being an owner of something gave these women authority when they were expected to uphold domesticity. Runaway slave advertisements were a platform for slave owning and plantation owning women to assert their position of authority to a predominately male readership.

As we conclude, it is important to ask if Early American White Southern female authority on plantations was challenged by their male counterparts. The answer is also simple, no. There was no real incentive for men to challenge female authority. Sharing patriarchal authority with a landed woman was a small price to pay to be married and keep property within the family. While landed women faced a value conflict between domesticity and dominance, dominance was chosen for them. Hiring overseers, shifting household responsibilities to domestic slaves, being delegates, entering a joint-mastery partnerships and even owning property were all mechanisms of dominance on plantations that landed southern women had at their disposal. Each mechanism shared a reliance on subordinating racialized and socioeconomic others to be effective. Additionally, each mechanism worked to sustain plantation patriarchy that depended on the unfreedom of racialized and socioeconomic others. Their freedom was the unfreedom of everyone else who was not white and wealthy on a plantation.

Thank you so much to Catherine for today’s post, I certainly learnt a lot about this earlier period in modern American history. It’s always interesting for us to hear about periods of time when women held a lot more power, but that last line is so powerful: “their freedom was the unfreedom of everyone else”.

Previous Blog Post: Energising Fashion: The Craze for Electric Corsets and Belts

Previous in Women’s History: Feeble or Fierce? Colonial Women of North America

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

Primary Sources

Chausée, Jacques. Traitié de l’Excellence du Marriage (Paris, 1690).

Mair, John. Book Keeping Method’iz; or, a Methodical Treatise of Merchant Accompts, According to the Italian Form (Edinburgh, 1736).

National Archives Identifier 2641471 “Dowry Gift of Slaves, Ann Taylor v. Thomas Hart Jr.”, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/documented-rights/exhibit/section1/detail/dowry-gift.html

Schulz, Constantine ,“The Papers of Eliza Lucas Pickney,” last modified 2023, https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/PinckneyHorry/default.xqy.

Windley, Lathan A, editor. Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History from the 1730s to 1790, vol 3. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1983).

Secondary Sources

Andrews, William L. Slavery and Class in the American South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Dresher, Seymour, Engerman, Stanley L, et al. A Historical Guide to World Slavery, edited by Seymour Dresher and Stanley L. Engerman. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Jones-Rogers, Stephanie. They Were Her Property, White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

O’Day, Rosemary. Women’s Agency in Early Modern Britain and the American Colonies (Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2007).

Smith, Daniel Blake. “In Search of the Family in the Colonial South” in Race and Family in the Colonial South, edited by Sheila L. Skemp and Winthrop D. Jordan (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009).

Stubbs, Tristan. Masters of Violence, The Plantation Overseers of Eighteenth-Century Virginia, South Carolina and Georgia 1670-1830 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2018).

Young, Jeffery R. Domesticating Slavery, The Master Class in Georgia and South Carolina 1670-1837 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).