Fashion is fashionable. It is ever-changing, inspired by culture, religion, and society, and every century has had its own “craze” where people go to extremes that are sometimes criticised by contemporaries, and sometimes by those looking back and wondering “what were they thinking?”. But one trend of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries was that for electric fashion: literally infusing clothes with electricity. Talk about shocking. (Sorry).

People have known about electricity, even if they didn’t know what it was, for millennia. And for as long as they’ve known about it, they’ve suspected it could have restorative power on the human body. At least two thousand years ago, ancient writers in the Roman Empire suggested that people suffering from illnesses like headaches should touch electric fish to be cured.

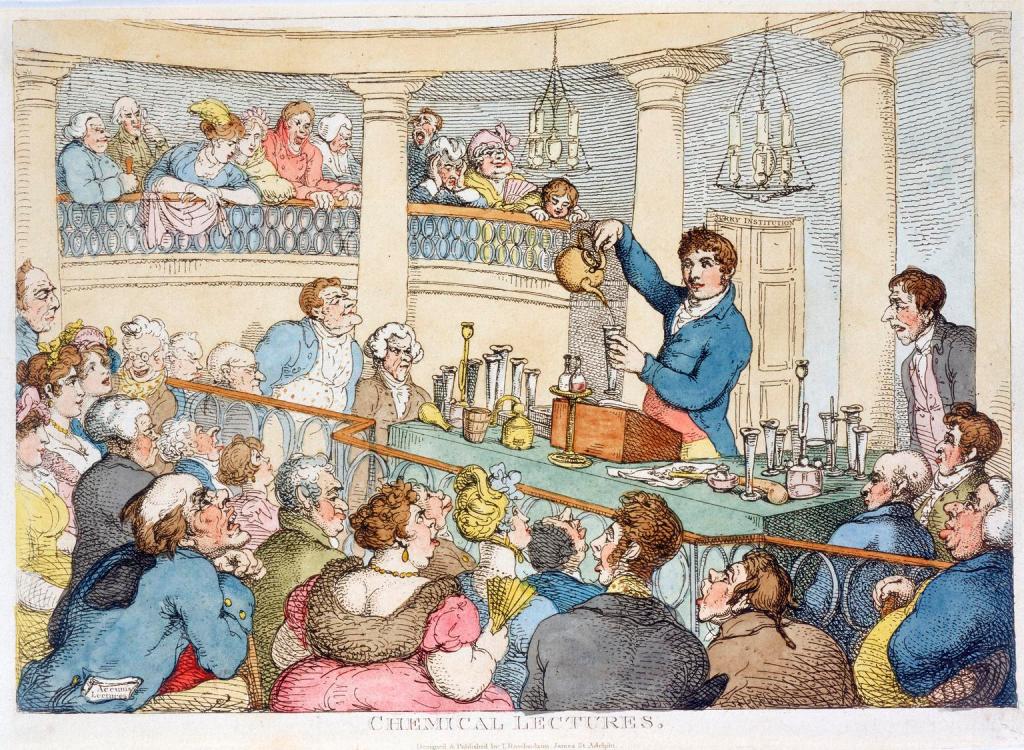

Through the centuries, scientists ran experiments with static electricity, trying to figure out what exactly the phenomenon was, until perhaps most famously American intellectual Benjamin Franklin made his own observations about lightning and electricity. The late 18th century saw a spate of experiments and studies about electricity published, and the following century huge advancements were made. Finally, electricity was an understandable, harvestable and useable resource, and innovation took off.

An electric motor was first invented in 1821 during a key period for popular imagination running wild with electricity. In the late 18th century, it had been noted that certain chemical reactions could create electricity. Meanwhile, in 1781, Italian surgeon Luigi Galvani was dissecting a frog near a static electricity machine and when the scalpel touched the frog’s leg, it jerked. Further experiments led to the conclusion that electrical current had moved the muscle tissue. In the ensuing decades, debate raged about what created life, and whether electricity was the ‘spark’ needed. Public displays of electricity ‘reanimating’ creatures became popular – some even using human corpses – and this led to a very serious belief that scientists were on the cusp of bringing the dead back to life. Most famously, this inspired a young Mary Shelley when writing her seminal book, Frankenstein, in 1816.

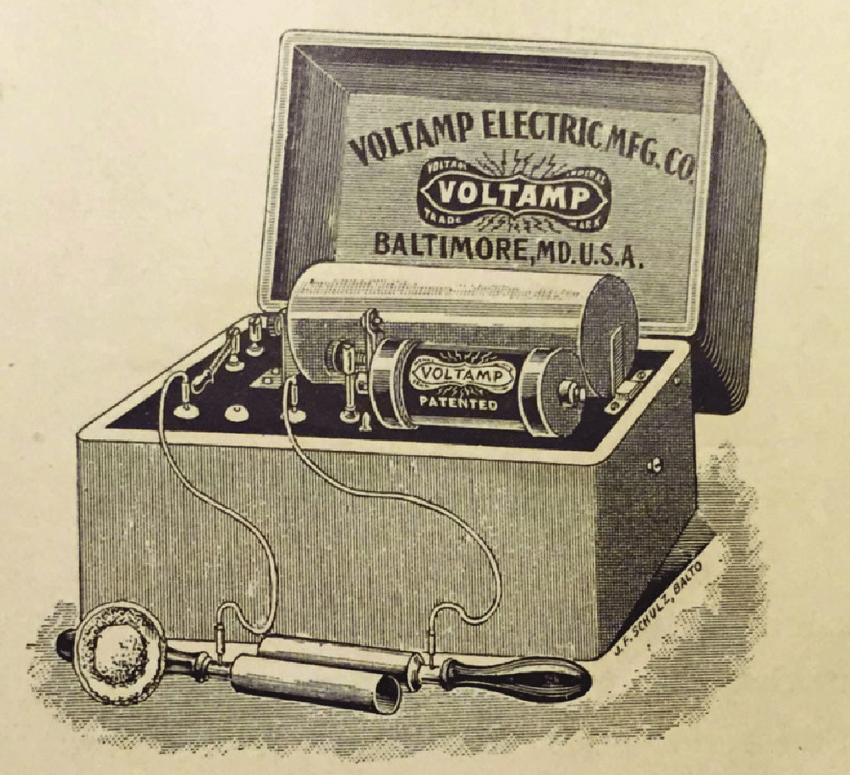

By the late 19th century, notions of bringing the dead back to life had faded somewhat, but there was still plenty of talk about how electricity could help human ailments. This led to a booming new trade in electric treatments. Though initially only offered by doctors, by the 1870s companies started selling batteries to the public so they could continue these treatments at home. These batteries came in a wooden box, and allowed people to shock themselves with a low-level current, but by the end of the century these portable cures were bemoaned by some doctors, who complained that only the medically trained should be conducting these treatments and that people were endangering their health by using them untrained and purchased from charlatans rather than under doctor supervision.

As these medical batteries became smaller and more portable, new ideas on how to provide an electric current to consumers were thought up by these supposed charlatans. By the 1880s, a myriad of products were infused with electricity that could be purchased from catalogues delivered to customers’ doors: toys, tools, home décor, furniture, household appliances and farming equipment. Living away from a city was no longer a barrier, with the extension of the railways and an ever-increasing postal service meaning products could come to you. Amongst this innovation, it was inevitable that fashion would also pick up the craze.

Although there were all sorts of fashion accessories one could purchase, from electric combs and hairbrushes to cure baldness or headaches, and electric insoles for gout and cold feet, two that particularly stand out were the electric corset and electric belt, marketed specifically at women and men respectively. These items of electric clothing were highly gendered and aimed to target specific complaints, and even hoped to tackle what was seen as a masculine crisis.

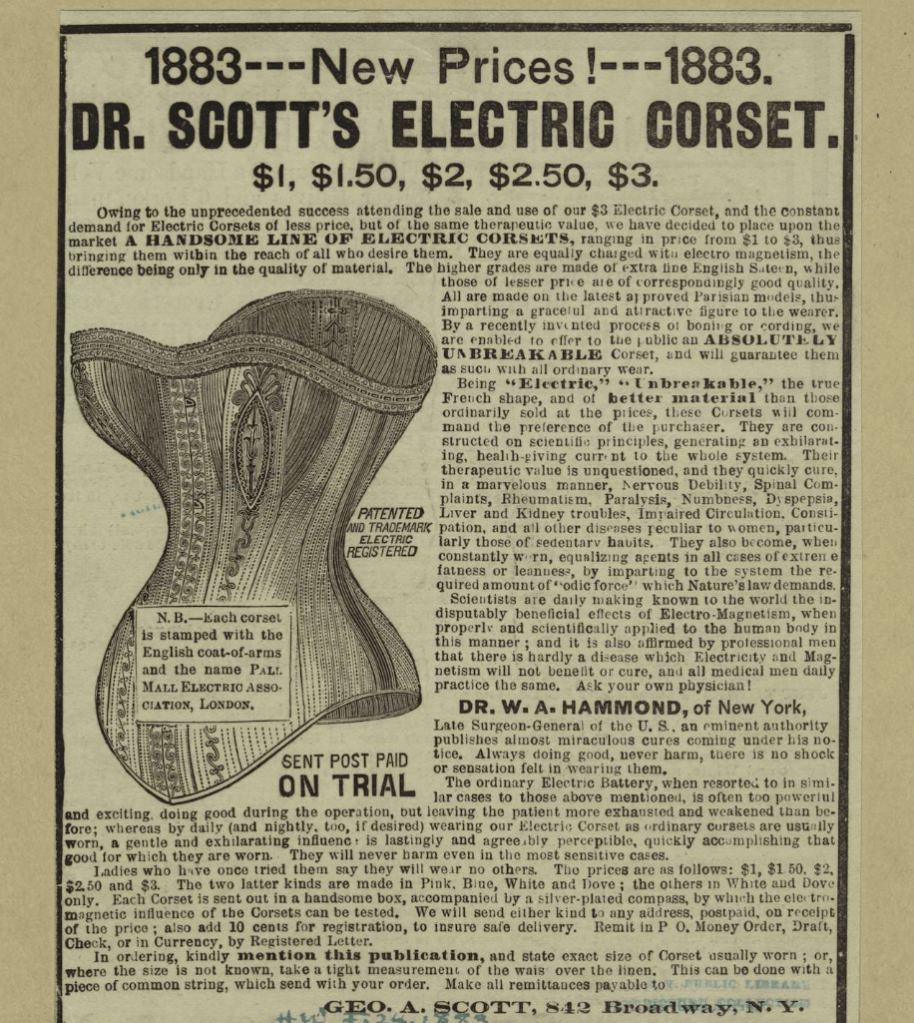

Corsets were still highly fashionable in western society as a way to shape a woman’s figure to a pleasing aesthetic based on curves and tiny waists. But now, with the help of electricity, feminine health issues could be simultaneously tackled. Alongside looking good, women could now feel good too. Corsets were lined with metals like copper and zinc, or used magnets, to try and generate low-level electric currents to convince wearers of their restorative powers. When used by women, these corsets claimed to help with menstrual cramps, weak backs, chest health, spinal complaints, paralysis, liver and kidney troubles, and a whole other host of ailments.

Understandably, these items became very popular, and numerous companies tried to take advantage of the sales boom. An 1883 advert by “Dr Scott” extolled the “unprecedented success” of its $3 electric corset, and explained it was now making more budget-friendly options from $1 and above to bring them “within the reach of all who desire them”. The advert uses emotive language to convince the wearer of its medical backing, saying their “therapeutic value is unquestioned”, that they “are constructed on scientific principles”, citing “scientists”, “medical men” and even name-checking Dr W A Hammond of New York, late Surgeon-General of the US. It is easy to see why people were influenced in the face of such medical claims, just as people have been swayed in the decades since by many other products claiming to be cure-alls.

However, doctors quickly turned on these products. Fed up with companies trying to profit off of medical treatments, they criticised products that had all the advertisement without any of the actual treatment. One review of an electric belt for both men and women sold by Mr C B Harness’ company in London was scathing, with Dr William Langran writing to The Electrical Review in 1888 that the circuit of metal discs in the belt appeared to be incomplete, and there were no signs of an electric current when placed on skin. He highlighted the problem with misinformation: “These belts… cause a highly imaginative portion of the public to believe in their efficacy as curative agents”.

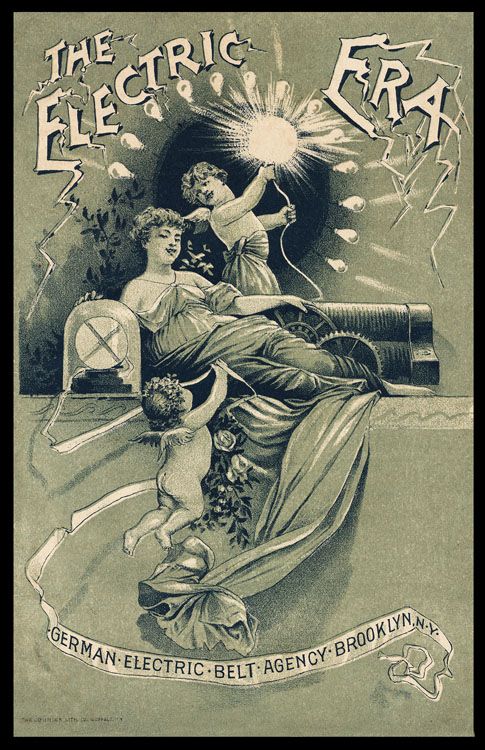

But whilst corsets were already a feminine product, and electricity merely enhanced them, it was the market for electric belts which really highlight gendered worries in Victorian society, both in the UK and the US. For about 40 years – between the 1880s and 1920s – these belts were touted as a way to save modern man. Electricity was natural, powerful, and could help the human body reach its full potential. It is no wonder, then, that this raw energy translated well to masculine power.

As opposed to women, who were merely having health and weight complaints solved by electricity, for men, electricity could enhance their body. It would regain their strength and improve their vitality. Adverts showed the ‘perfect specimen’ of men with large muscles and toned bodies. Importantly, most of these belts claimed to improve men’s sex drive and sexual performance.

At this time, there were great worries in society about men physically declining. There was moral panic about masturbation, with the idea that this was sapping men of their vigour and strength, and infertility and erectile dysfunction were seen as significant problems that were created as a result. Electric belts seemed to be universally considered the solution. Electricity was powerful, it stimulated muscles, and cured a plethora of problems, so it made complete sense that it could revitalise men too.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Most belts were created with pouches for the testes for direct application, and looped through with zinc and copper wires. Early belts dispensed very small charges by being soaked in vinegar then pressed to skin, but later on more intense charges were gained by plugging the belts in to electrical currents.

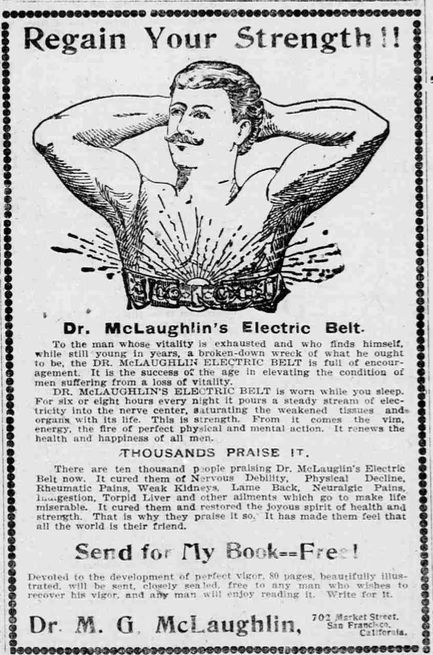

Of course, being the Victorian era, it was unseemly to talk about sexual complaints in public. Adverts therefore had to use coded language, which would have been widely understood, to explain the medical benefits of these belts. Such language can be found in a 1901 advert targeted at men “whose vitality is exhausted”, explaining that by wearing their belt overnight they will gain “the vim energy, the fire of perfect physical and mental action”. Sexual power could thus be restored, and with it a perfect, masculine body.

Again, a huge appeal was found in being able to order such products to your door. The same advert reassured men that their information book would be sent “closely sealed”. Another brochure created by Zardon the same year wrote on its front page, “Do you care to have your family physician whisper around that you are not as good a man as you once were? Do you wish to have the druggist laugh at you when getting a prescription filled?” This at once played into fears that men were less than they should be, that they required help, and that rather than go to a doctor for advice lest their inadequacies become known, they should purchase a product from a private company who would keep their secrets instead.

Eventually, the electricity hype died down. During the First World War, electric medicine began to be rejected. Medical schools stopped teaching electrotherapy, and fewer articles were published on the matter. By the 1920s, most interest had ceased. This was likely due to a combination of factors, including increase crackdowns on “quack” treatments by governments and regulating bodies, a shift towards psychological treatments for diseases, and the fact that these treatments did not always work. As such, electric belts faded from the market, and changing fashions removed even normal corsets from shops. But for a time, public imagination had been well and truly captured. Electricity was the miracle element, capable of bringing light into homes without fire, of powering machines without physical labour, of curing any disease, and even of maybe breathing life into the dead. Electrical corsets and belts capitalised on this obsession, blending fashion and function to improve the lives of their wearers – whether it truly worked or not.

Previous Blog Post: Pontefract Castle: The Key to the North

Previous in Historical Fashion: Jewellery: The Eyewitness of History

You may like: Historical Fashion: Victorian Women’s Clothing

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/the-science-behind-mary-shelleys-frankenstein/

https://underpinningsmuseum.com/museum-collections/electric-corset-electropathic-belt-promotional-materials-by-harness/

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/11/electric-corsets-the-original-wearable-devices/507230/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/48555525?searchText=%22electric+corset%22&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3D%2522electric%2Bcorset%2522%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Adb020c6e90ba1bb22821a44420a5f015&seq=8

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3527257?searchText=%22electric+corsets%22&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3D%2522electric%2Bcorsets%2522%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3A878a299ed8b4b51296105add3f4804ab&seq=8