It’s been a little while since I’ve written about a castle, despite the plethora of incredible castles in England where I live, let alone ones further afield. Last month I visited Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire, so I thought it was a perfect opportunity to pick this series back up! Pontefract Castle was one of the most important in the country throughout the medieval period, up until its destruction in the aftermath of the Civil War, and today it is just a shadow of its former grandeur. So what exactly was so impressive about it?

As is the case with many of the castles in England, Pontefract Castle traces its roots back to the Norman Conquest. Duke William of Normandy successfully pushed his claim to the English throne and brought his loyal nobles with him to essentially colonise England. Up to this point, England had been filled with Saxons, Angles, and various groups of Norse, who had made up the ruling classes. But the Normans pushed the men out of leadership, and inter-married with local noble women, and they brought their own culture and language with them. There was plenty of discontent about this, and it took decades for William and his heirs to subdue the nation. Thus, castle building was a high priority of his. Previously, fortifications had largely been wooden, but William brought imposing, stone castles as a way to intimidate the locals and protect his interests. During his two decades on the throne, it is estimated that he oversaw the construction of hundreds of castles.

One of William’s key allies who fought for him at the Battle of Hastings was a man called Ilbert de Lacy, and William rewarded him generously by granting him a significant portion of land in northern England – the Honour of Pontefract. Amongst this land was an Anglo-Saxon burial ground and manor on the top of a rock which was in the perfect position to expand. Within a few years of the Norman Conquest, records show a castle being constructed on the site, and it was recorded in 1086’s Domesday Book. The timing was no surprise: construction likely began around 1070, just after William’s infamous Harrying of the North. After a major rebellion in northern England, William had spent the winter of 1069-1070 razing much of it to the ground, destroying crops and animals and causing mass starvation. It made sense he would want one of his loyal friends to start building a castle to keep the local population in check afterwards.

Ilbert and his family continued working on Pontefract Castle for many years afterwards, expanding it and making it a formidable fortress. But though Ilbert had been a close and loyal friend of William’s, his descendants had a more fraught relationship with the Crown. At various points the Honour of Pontefract was confiscated from Ilbert’s son, then regranted, but the tipping point was in 1211 when the current holder, Robert de Lacy, died. King John, who ruled at that time, confiscated the castle, and made Roger’s heir, John, pay a huge amount of money to regain his inheritance. John was furious that what should have been his rightful inheritance was taken from him through greed, and so he joined other rebel barons in a fight which eventually led to King John being forced to seal the Magna Carta.

After this, relations settled a little, and the de Lacys continued their tenure of the Honour and castle of Pontefract. They continued to expand, building a highly impressive keep within the walls to an unusual design; it is in a quatrefoil shape of overlapping circles, rather than a square shape, which is rare.

In the early 1300s, the keep finally moved out of the de Lacy family through marriage of its female heir, Alice, to Thomas, Earl of Lancaster. Alice had become heir after the tragic deaths of her two brothers – one of whom fell from a parapet at Pontefract Castle – and Thomas was the grandson of Henry III of England and son of the Queen of Navarre, so a very powerful man. Their wedding agreement ensured that Alice’s vast inheritance would go to Thomas and the royal family even if the couple had no children together. They had a highly unhappy marriage, and Thomas was eventually executed for treason at Pontefract Castle. Although Thomas’ lands forfeited to the Crown, Alice’s inheritance should have returned to her. However, Edward II (king at the time) did not want to lose such a vast amount of land and wealth, and he imprisoned Alice and threatened her until she signed over most of her lands to the king. Thus, the de Lacy’s 150-year ownership of Pontefract Castle came to an ignominious end.

After this time, the castle passed into the control of the earldom and later duchy of Lancaster, including one of the most powerful men of the late 14th century, John of Gaunt. John was very fond of the castle, making it one of his personal residences, and he spent a significant amount of money upgrading it into a royal home. However, it was again to become a place of death at the turn of the century, when the overthrown and imprisoned King Richard II died at the castle. As the castle had moved into the possession of John of Gaunt’s son and heir, Henry Bolingbroke, when Henry succeeded his cousin as King Henry IV, the castle became part of the royal estates.

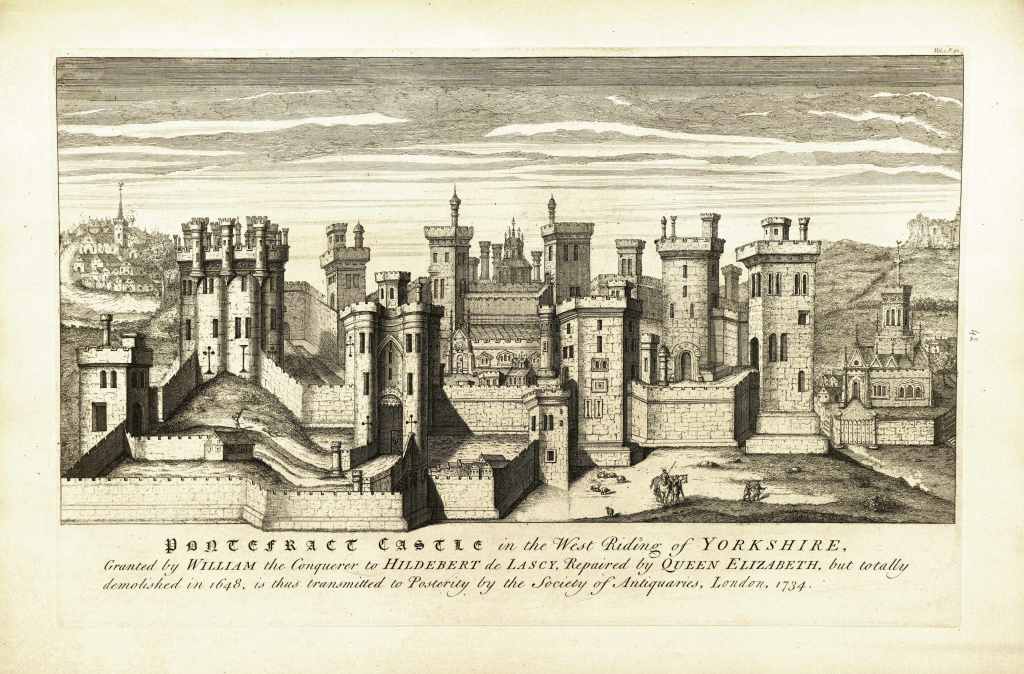

Pontefract Castle had become, over the centuries, one of the strongest fortresses in the north of England. With inner and outer baileys and barbicans, curtain walls, multiple towers, and a significant keep, as well as its own chapel, by the Early Modern period the castle was unassailable. It continued to be an important hub in royal history: in 1483, Richard III executed the son and brother of Queen Elizabeth Woodville there, whilst in 1536 the castle’s guardian was executed for treason after handing the castle over to rebels taking part in the Pilgrimage of Grace, a Catholic rebellion in response to the break from the Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It is also supposed to be the site of Henry VIII’s fifth wife, Catherine Howard’s, first act of adultery.

Perhaps one of the biggest chapters in the castle’s history, though, comes from the English Civil War. Being such an important site – seen as “the key to the north” – it came under siege three times. Initially under royalist control, the garrison surrendered during the second siege after news arrived of Charles I’s defeat at the Battle of Naseby in 1645. However, the Royalists continued to try and fight for their king, and so in 1648 they hatched a cunning plan. Knowing the castle was unassailable by brute force, they used cunning instead. After hearing some of the Parliamentarian forces trying to requisition beds in the town, some Royalist troops disguised themselves and brought beds up to the castle, in a trick worthy of the Trojan Horse. Once inside, they managed to take control of the castle and hold it for 9 months, only surrendering when Charles I was executed.

The impact of the Civil War sieges is evident on the ruins today, where cannonball dents can be seen. During conservation work in 2016, seven cannonballs were found still lodged inside the outer wall of the castle almost 1 metre deep. This demonstrates just how strong the castle was, that it still did not fall under such pressure. The physical evidence is corroborated by a key source for this period, the diary of Nathan Drake who was at the castle during the 1644 siege. Here, he wrote that in just the space of a few days (17th to 21st January) 1,363 shots were fired at the castle. Despite this huge barrage, only one tower collapsed, and it still did not give the attackers access to the castle – even in the ruined state of the castle today, the curtain wall of the collapsed tower still stands around 5 metres high.

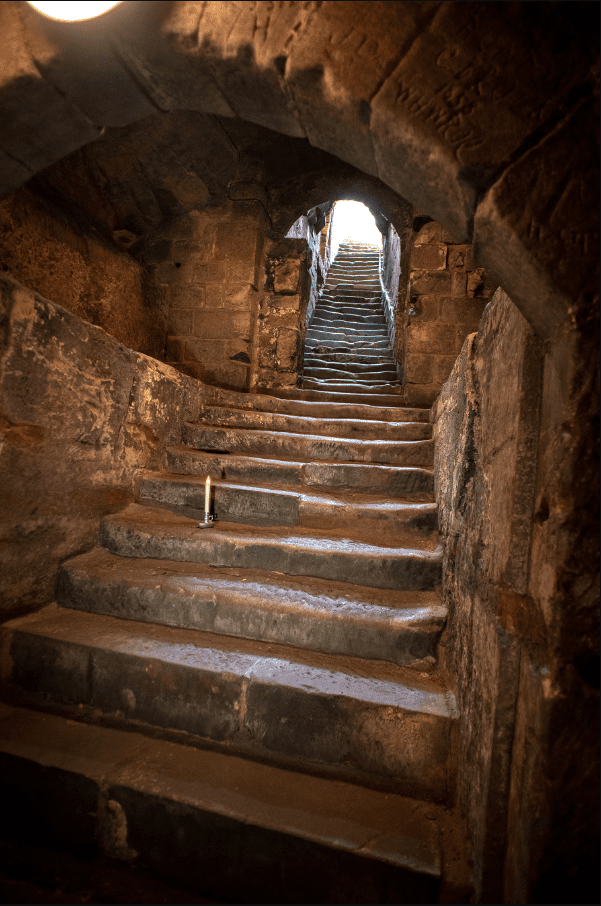

With the ending of the Civil War, and Oliver Cromwell’s seizing of power, the almost six-century dominance of Pontefract Castle came to an end. Cromwell was keen to destroy the castle, which he considered one of the strongest garrisons in the country, and he gained the support of the people who lived in the surrounding town, who had suffered greatly from pillaging armies. In March 1649, Parliament gave orders that it should be ‘totally demolished & levelled to the ground’. Much of the castle was dismantled and sold off to be reused as building material, though a surprising amount still remains. Parts of the curtain and inner wall survive, as well as foundations of buildings like the chapel. Underground, the eleventh-century cellars survive as do the dungeons.

Despite its dismantling, the site of Pontefract Castle continued to be used by locals for other, perhaps more surprising uses: liquorice. Liquorice arrived in England in the eleventh century, and for centuries it was used as a medicine. From at least the 17th century, Pontefract had been growing the plant, but it soon turned into a major industry for the town. By 1720, a local family, the Dunhills, rented out the grounds of the castle in order to grow liquorice and store the plants in the castle’s dungeons. The conditions at the castle were perfect for the plant to thrive, and George Dunhill was able to use this success to revolutionise the liquorice trade.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

In 1760, he completely changed the format of liquorice. What had previously been a dissolvable, medicinal pastel, he now added sugar to and turned it into a chewable sweet which became known as the Pontefract Cake. The family continued to work out of the castle for more than a century. As the Victorian era arrived, the use of the castle and its grounds changed again. A local wealthy woman named Jeanette Leatham created pleasure gardens at the castle, and became involved with the museum at the castle.

Many of the walls of the castle still stand several metres high, as do some of the towers. Author’s own photos.

Today, the castle is still owned by the Duchy of Lancaster, but it is a heritage site managed by Wakefield Council and in receipt of funding from bodies like English Heritage and Historic England. It underwent major conservation in 2016 which uncovered multiple unknown structures to the south of the gatehouse, and work is still pending to secure these remains. The castle is open to the public for free, and guided tours of the castle and the dungeon are run for a charge. There is a visitor centre with some display cases of artefacts, a playground, and a herb garden, as well as regular programmes of activities and events. It continues to be a draw to the area.

Pontefract Castle has a history that spans almost a millennium. Built as a symbol of terror and oppression, it spent centuries at the heart of royal conflict and intrigue. Certainly one of the most significant castles in the country, it was an imposing marker on the horizon and turned out to be impenetrable. In fact, it was this very quality that led to its ordered destruction. But its tearing down did not equal its demise, and it found a new lease of life in an unexpected industry, as a hub for liquorice. Today, its ruins still stand in defiance of all that was done to it, continuing to draw visitors from far and wide. Pontefract Castle, the key to the north, still shares its many stories with those who wish to listen.

Previous Blog Post: Jewellery: The Eyewitness of History

Previous in Castles: Windsor Castle, Heart of the Monarchy

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://www.wakefield.gov.uk/museums-and-castles/pontefract-castle/pontefract-castle-stories

https://projects.digventures.com/pontefract-castle/background/a-brief-history-of-the-castle/

https://projects.digventures.com/pontefract-castle/background/how-the-dig-began/

https://www.wakefieldexpress.co.uk/whats-on/things-to-do/in-pictures-inside-pontefract-castles-terrifying-dungeon-where-civil-war-prisoners-were-left-to-languish-4470706

https://www.bbc.co.uk/travel/article/20190710-the-strange-story-of-britains-oldest-sweet

2 responses to “Pontefract Castle: The Key to the North”

Fascinating- hence the Pontefract cakes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! All makes sense now!

LikeLike