Today we return to an old favourite series of mine, looking at the history of mythical creatures. In recent years, the unicorn has experienced a true revival, representing both LGBTQ+ communities and becoming a fan favourite of young children. But the unicorn was just as popular in medieval Europe, appearing countless times in artwork and heraldry. So where did the idea of this creature come from, and why did it have such a hold?

It is thought that the concept of a unicorn originates from sources in the Indus Valley (covering parts of Pakistan, India and Afghanistan) around 2,000 BC. Here, it is found on various artefacts as a cow-like creature with one single, long, curved horn. From there, writers in ancient Greece heard stories, writing about single-horned wild asses from India from the fifth century BC onwards. As time went on, the stories of these animals became conflated with creatures called re’em described in the Bible. This animal almost certainly referred to a type of wild ox or antelope, but in translating from Hebrew to Greek, where there was no equivalent word, it became monokeros and then eventually translated into Latin as unicorn.

Now that the unicorn had found authority in the Bible, and following already circulating stories of its existence, the unicorn took on a mythos of its own. Pliny the Elder described the unicorn as having a body resembling a horse, a head like a stag, feet like an elephant and a tail like a boar. But by the following century, what was to become the greatest authority on unicorns was published. The Physiologus was a second-century Alexandrian compilation of beasts, and it introduced the most enduring legend of the unicorn:

A small animal like the kid, is exceedingly shrewd, and has one horn in the middle of his head. The hunter cannot approach him because he is extremely strong. How then do they hunt the beast? Hunters place a chaste virgin before him. He bounds forth into her lap and she warms and nourishes the animal and takes him into the place of kings

Michael J. Curley, Physiologus: A Medieval Book of Nature Lore, cited in The Unicorn Tapestries: Religion, Mythology, and Sexuality in Late Medieval Europe

Initially, the unicorn was seen as an evil creature. Its large horn was seen as synonymous with pride or lust, and unicorns were thus associated with vice and demons. In one version of the Physiologus, the virgin offered the unicorn her breasts which he began to suckle and “conduct himself familiarly with her”. But by around the twelfth century, the unicorn took on significant Christian symbolism which it was to carry for the rest of the period.

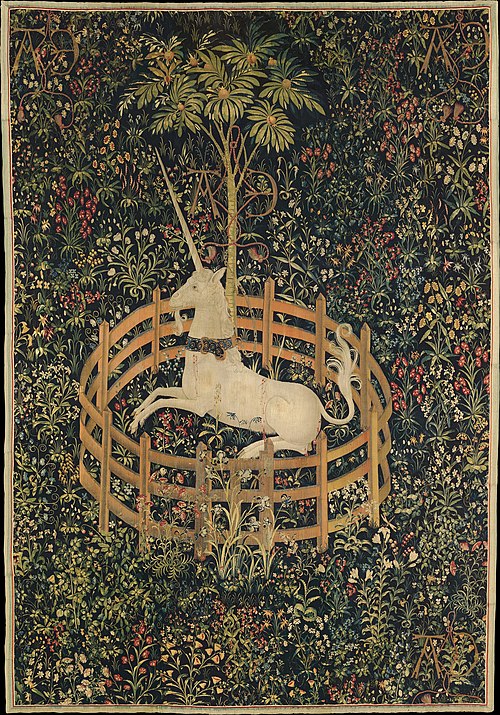

A dangerous creature tamed by a virgin, only to be murdered by hunters, found an easy comparison to the story of Christ. It became exceedingly popular in artwork – particularly tapestries – to depict the hunt of the unicorn, imbuing symbolism of the Incarnation of Christ and his Crucifixion. This is exemplified by pieces like The Unicorn Tapestries, made right at the end of the period (1495-1505) where the classic unicorn hunt story appears alongside other Christian allegories, such as in one section where the unicorn is surrounded by twelve hunters, one of whom points to the unicorn reminiscent of Judas’ betrayal, or where the killed unicorn is brought back to the castle wearing a wreath of oak branches with thorns, like Christ’s Crown of Thorns. Other pieces instead linked the hunt of the unicorn to the Annunciation, where the hunter and virgin become the angel Gabriel and Mary, and thus the hunt and taming becomes the conception of Christ.

Alongside the unicorn’s heavy religious symbolism, it also found itself an important role in secular society. Despite its exceeding popularity in artwork, it appears infrequently in the textual record, only being found in one known medieval romance, Le Chevalier du Papegau or The Knight of the Parrot. It did, though, take on a general air of romance – almost inevitable, considering its centuries-long association with virgin women – and it appeared in other written works under this association. The twelfth-century Carmina Burana, a collection of poems and dramatic texts, feature unicorns, as does a piece written by renowned thirteenth-century troubadour Count Thibaut IV of Champagne, where he compares himself to a unicorn falling deeply in love with a woman. Over time, the unicorn therefore also became associated with courtly love and with marriage, and it is thought that the highly famous Lady and the Unicorn tapestry set was commissioned by a member of the powerful Le Viste family of Lyon to commemorate a marriage.

Two panels from The Hunt of the Unicorn, showing Christ-like symbolism. Met Museum.

Another appeal of the legend of the unicorn came from real-world artefacts associated with the creatures. Though rhinoceroses were well-known, narwhals were less so, and the beautiful, long horns of the creatures made perfect substitutes for unicorn horns. One of the stories of the unicorn was that its horn had purifying qualities, and by dipping its horn in water it was able to nullify poison, cure disease, or otherwise protect. Obtaining these protective horns thus became a major medieval trade, and every major court in Europe had objects made from or featuring these unicorn/narwhal horns. It was particularly popular to have drinking vessels with pieces of horn, to protect the ruler from ingesting any poison.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

As heraldry took off, so too did nobles’ desire to associate themselves with the unicorn. The unicorn represented Christ, the Virgin Mary, chivalry, romance, nobility, suffering, salvation and more. The appeal was clear. Nobles across Europe incorporated it into their Coats of Arms, even at the highest level; the Scottish royal family used a unicorn to represent them from at least 1426, and it is still used to represent Scotland to this day.

Interest in the unicorn continued into the Renaissance, but by the seventeenth century this began to wane. No longer did people believe that the creature could exist, or in the protective property of the horns. The unicorn fell into the background, to be revived by Victorian interest in all things medieval and championed into the modern day.

The unicorn is a creature of mystery and beauty. Its legend has lasted two millennia, and its story remained surprisingly unchanged throughout the medieval period. Despite being depicted in art and literature for centuries, the core idea was consistent: a strong, elusive creature with a single horn, impossible to tame but for the appeal of a virgin woman. This one story found easy footing in Europe during this time, a place of fervorous religious belief and wideswept chivalric romanticism. The unicorn was both the poet devoting himself to a noble woman, and Christ sacrificing himself for the sins of the world. Its horn could protect people from the gravest poisons, whilst its visage adorned palaces and castles. And its appeal is just as strong today, even if the story has now evolved.

Previous Blog Post: A Brief Moment of History: Humanity’s Worst Year Ever?

Previous in Mythical Creatures: A History of European Werewolves

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

The Biblical Unicorn in Late Medieval Religious Interpretation

The Unicorn Tapestries: Religion, Mythology, and Sexuality in Late Medieval Europe

Heroes and Marvels of the Middle Ages

Imaginary Animals: The Monstrous, the Wondrous and the Human