Many of us are aware of the Reformation, and how it completely changed the landscape of Europe across the 16th century and beyond. But not so many are aware of the Catholic Church’s response to the Reformation, and how it tried to reform the Church and lure people back to Catholicism, whilst re-asserting its identity in the face of Protestant branches. I’ve always found this period of time so fascinating, and was lucky enough to study it many years ago, so I’m so excited to welcome our guest author for this month who is going to enlighten us to how the Catholic Church used art as part of this movement. A big welcome to Molly, and I’ll let her introduce herself before we get started!

My name is Molly Lindo and my love for history came from my late grandfather, who first sparked my passion for history from a young age, recalling his many adventures in the military in the 1960s and his travels after his service. My passion for the subject only flourished during school and then I went on to study it university. I now have a BA in History and an MA in Cultural History from the University of Chichester.

In the 16th century, Protestants hated Catholicism, especially its use of images, believing they were ‘wrongheaded’ idolatry. After a series of violent iconoclastic riots in northern Europe, Pope Paul II urgently summoned the Council of Trent (1545-1563) at the defence of Catholicism – essentially a huge meeting of the clergy in Trento, northern Italy, where matters of Catholic doctrine were discussed. Sacred images were the subject of the twenty-fifth session in December 1563 and the ‘Decree on Sacred Images’ was born. It was decided that images would be used as ‘vessels’ to usher the faithful against the profane and towards devotion, and to encourage the memory of religious prototypes.

The Catholic Church plunged itself into the Counter-Reformation (1545-1648), its zealous reinvigoration to ‘counter’ the Protestant Reformation and its criticisms of the papacy. Baroque artists “internalised the spirit of Catholic reform” and the result was the combined effect of total works of art that enlightened all the senses. In collaboration with artists, the Decree instructed all bishops to ensure all sacred images educated the faithful on true Catholic doctrine and practices, such as intercessory prayer. Nothing disorderly, misleading or profane; no false doctrine; and no impurities were to be displayed in images.

Every corner of the expanding Roman Catholic world was filled with decapitated saints, crucified Christs and enraptured Virgin Marys of the Baroque and with increased vigour and conviction. Baroque art overwhelmed the senses with its use of intense emotion, radical realism and dynamism. While art of the past thrived, new categories of subjects proliferated to rebut Protestant heresies, such as paintings of sainthood, biblical scenes, martyrdom, and the Cult of the Virgin Madonna.

The realism and visceral drama of Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin (circa 1605-1606), portraying several figures hanging over the Virgin’s lifeless body in devastation and sadness, is a stark contrast to Annibale Carracci’s colourful and triumphant Assumption of the Virgin (1588-1590), where many holy figures gaze upon the Virgin in complete shock as she ascends from her earthly existence to Heaven. For the two leading artists of the time, they had very diverse painting styles. Carracci’s Virgin radiates light and harmony, whereas Caravaggio’s Virgin is less magnificent and more realistic, perhaps more accessible to the viewer, set in a dramatically lit and cropped space.

Mary’s role as the Mother of Christ also flourished as a point of connection with the viewer – the role of a mother was a relatable and realistic one. Carracci’s Montalto Madonna (circa 1598-1600), Artemisia Gentileschi’s Madonna and Child (circa 1613-14), and Tanzio da Varallo’s Madonna con Bambino e I Santi Francesco e Carlo Borromeo (1631) and Madonna dell’incendio (1614) are all important displays of Mary in her maternal role. While Tanzio celebrates majesty, Carracci and Gentileschi innovatively explore the mundane life as a mother, for instance, Gentileschi’s Madonna is ready to nurse her son as he turns and caresses her face. Caravaggio’s Madonna of Loreto (1604-1606) shows how powerful realism was in the art world – viewers of the time, who largely could not read or write, would have felt so connected and overwhelmed by these paintings at a time when meaning and symbolism trumped the literal sense. The beautiful canvas depicts the moment pilgrims arrive to worship Mary and Jesus – its seems quite an ordinary scene with only the halo, the large child figure and Mary’s gestures away from the infant Jesus separating it from reality.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, most people could not read and write – literacy levels were incredibly low, especially in Catholic strongholds Italy and Spain. In 1601, 23% of the Italian population could read and write, and only 5% in Spain. So when Baroque artists took to painting biblical scenes, they were both delighting the senses and disseminating Catholic theology. Scenes of the Nativity and Adoration of the Magi, the Taking of Christ, and the Three Marys at the Tomb all flourished in the Baroque era.

Caravaggio’s The Taking of Christ (1602) and Nativity with Saint Francis and Saint Lawrence (1609), Gentileschi’s Adoration of the Magi (circa 1635-37), Carracci’s Three Marys at the Tomb (circa 1600) and Veronese’s The Adoration of the Kings (1573) all show the importance of portraying the Bible on canvas. For the clergy, it was a way to educate the uneducated flock. The Decree even states that images had to be so powerful that they were “continually revolving in mind.” Sacred images were a major form of indoctrination for the Catholic Church, like we see how propaganda was used in Nazi Germany or the Soviet Russia. For example, Caravaggio’s David with the Head of Goliath (before 1610) and Tanzio’s David and Goliath (circa 1625) both depict the important allegory of having courage and determination when one’s faith is placed entirely in God alone. What sets Baroque artists apart is their clever use of light and dark, realism, dynamism and tightly cropped compositions, but beyond the style, these new innovations made scenes so real that they were almost unfolding before the viewer’s eyes.

The act of divine intervention by miracles of God was also an important feature of Catholic theology and the Decree instructed that all clergymen must teach their congregation the benefit of praying to saints “offer up their own prayers to God for men.” Paolo Veronese’s Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto (1572) and Tanzio da Varallo’s Battle of Sennacherib (1629-30) are both powerful examples of how artists integrated Catholic practices into their paintings to produce magnificent yet accessible scenes for all. Veronese celebrates the defeat of the Ottoman Turks against the fleets of the Holy League (basically, a fleet of loads of Catholic nations and principalities including Spain, Venice, and the Papal States) and Tanzio depicts the triumph of Hezekiah, the King of Judah, against the Assyrian King Sennacherib. Again, the clever and innovative use of light and dark (also known as tenebrism) accentuates the central role of saints interceding on behalf of God. Veronese depicts the beneficent rays of the Virgin Mary which shine down from Heaven and illuminate the victors’ ships, while darkness torments the Turkish fleet. Tanzio’s angel is illuminated by the presence and protection of God as he plunges into the darkness of bloodshed.

Saints, martyrs and Jesus Christ were also to be portrayed in art, essentially as role models of devotion and sacrifice so that Catholics “may order their own lives and manners in imitations” of them. The worship of saints was central to the Counter-Reformation and Baroque ideals – such as exciting senses and emotions – only served to remind viewers of the importance of this message.

The worship (or invocation) of saints in times of need was a central Catholic practice and so there were devotional cults of various saints. For example, the cult of Saint Roch began in the latter half of the 15th century in northern Italy as a protector against the plague after the Black Death had ravaged Europe in the previous century. Carracci’s Saint Roch Giving Alms (1587-95) is not as emotionally intense as Tanzio’s San Rocco (1631) but is not painted in his characteristic classical style by any means. Carracci paints the figures with much realism, such as the physical gestures of the poor reaching up to Saint Roch to retrieve alms. Even Roch himself looks rather ordinary – its only his raised position on a building and the glowing halo surrounding his head that separates the saint from the ordinary people, acting as reminders of his role as a divine intercessor. It’s not hard to see why Baroque art played such a central role in the Counter-Reformation – artists made holy figures and scenes so relatable and realistic, and so accessible that viewers felt apart of the canvas. Tanzio’s San Rocco is very similar in this respect, with Roch raised above his flock but below God. Tanzio’s use of tenebrism adds to this, with rays of light illuminating the saint’s face in affirmation of the presence of God. And Tanzio added the dog of Saint Roch (who brought him bread and remained at his side); this symbolism furthers the message of fidelity and loyalty to the Catholic Church.

In Christianity, martyrdom was pretty up there in terms of noble religious sacrifices so worshipping martyrs was central to the Decree. It was important to raise saints and martyrs unto eternal life as models of devotion for Catholics to follow. The veneration of martyrs was a long-held practice since early Christianity (dating back to the 2nd century) and the Counter-Reformation sought to reinvigorate commemoration of the holy. Derived from the Greek word ‘martus’ (or ‘witness’), the term ‘martyr’ was adapted and narrowed by Christians to refer to those who had born witness to their faith at the ultimate cost of their existence on Earth. An act of heroism and penance, martyrdom was the biggest sacrifice for salvation in Heaven.

Saint Peter was the first pope of the Catholic Church and had an inner intimacy with Christ which made him a central figure in Catholic art, appearing in countless conversion and martyrdom paintings. Caravaggio’s The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1601) depicts his martyrdom, which was instructed by Emperor Nero for his role as a Christian leader in pagan Rome. In the Acts of Peter, it states that Peter was crucified head downward at his own choice as he did not consider himself worthy to die in the same manner as Christ. The viewer is immediately confronted with the physical effort of crucifying Peter upside down and his suffering, for example, the discomfort and pain emanating from his face as he tenses his impaled hand. The realism, the dramatic use of light and dark and the movement of the painting built along strong diagonals adds to the importance of Peter’s sacrifice.

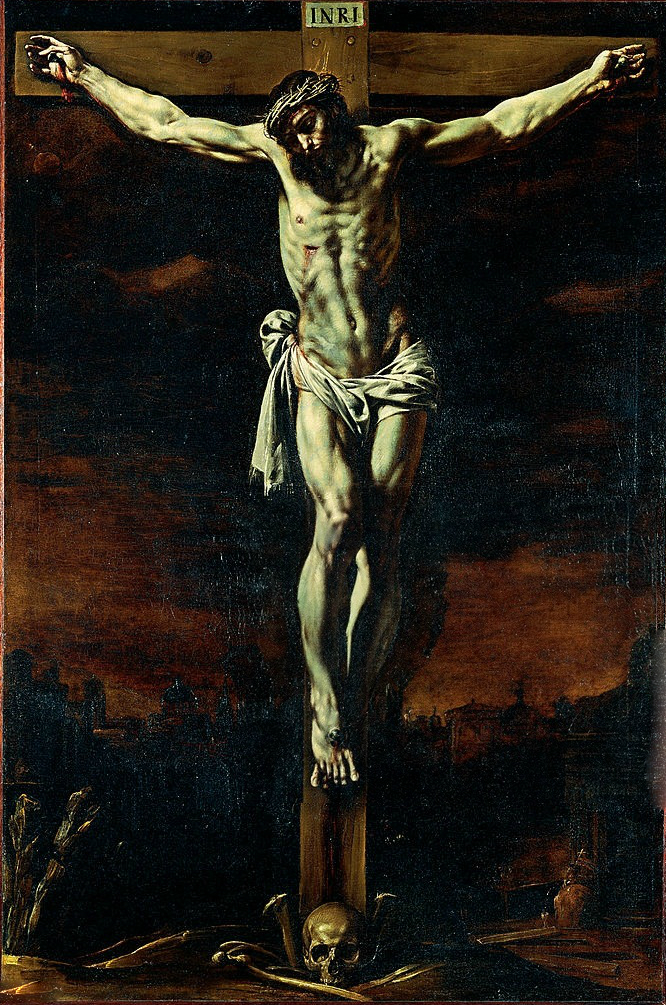

Baroque artists also began painting Jesus Christ with a renewed passion and intensity to emphasise his suffering and sacrifice to save man from sin. Basically, Catholic doctrine taught that Christ only descended to be born and crucified for the sake of man, who had succumbed to sin by his own fault from the time of Adam. So, the Council of Trent looked to artists to move Catholics into devotion for the atonement for their role in Christ’s sacrifice.

Carracci, Caravaggio and Tanzio brought Christ’s sacrifice onto canvas in a never-before-seen sense of drama and harrowing intensity. Carracci’s Crucifixion with Saints (1583) is painted with a rugged sense of realism, and his Christ Crowned with Thorns (1598-1600) conveys the agony and humanity of Christ’s suffering, through the infirm and weakly contortion of Christ’s body and his desperate gaze. The antithesis of Carracci’s classical and idealistic style, Caravaggio’s The Crowning with Thorns (before 1607) offers the viewer unmediated realism. Both Carracci and Caravaggio show the toll of physical affliction, for example, the thorn crown piercing Christ’s head and the flowing streams of blood, but Caravaggio takes it a step further. He depicts more of the physical intensity of the act: the muscular strain on the bodies of the two men behind Christ, who himself is painted as a limp, weakened figure, almost lifeless, slumped to one side, looking downwards in sheer hopelessness and pain.

It would be incredibly wrong of me not to mention Tanzio’s Crucifixion (1630). Not much is known about Tanzio’s life, his whereabouts, the chronology of his works. And because of this lack of information, he seems to have slipped through the sands of time. Upon studying his artworks, however, it was made glaringly obvious to me the fundamental influence of Caravaggio on Tanzio’s artistic production. Tanzio’s radicalisation of the depiction of Christ was completely unprecedented. At the time, this painting was the apotheosis and reinvigoration of all paintings of the Passion that had come before. The canvas is overcome with an all-pervasive emotion, radical intensity and piercing theatricality. The anatomically perfect body of Christ dominates, hanging lifeless from the Crucifix, hands and feet bloody from being nailed to the Cross. The scene is harrowing, passionate and psychologically intense, and the memento mori (a symbol of the inevitability of death) at the foot of the Cross only adds to the already overwhelming emotion of the scene.

The Decree also stated that paintings of Christ, the Virgin Mother and other saints were to be displayed in temples to enhance devotion so that worshippers “may be excited to adore and love God.” Artists began to look at the idea of intense emotion and spiritual experience in the Catholic world, bringing innovative genres of art to the sacred Baroque. The feelings of ‘incredulity’ and ‘ecstasy’ were explored and artists appealed to all the senses to excite the faithful into devotion and piety. Most importantly, the idea of spiritual experience and visceral emotion were accessible to all and so offered a connection with the divine figures depicted on canvas.

Veronese’s Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (1565-70) depicts the dream Saint Catherine of Alexandria had after her baptism, where the infant Christ took her as his celestial spouse; she awoke to find a ring on her finger and kept it on for the rest of her life as an emblem of her faithfulness and fidelity to Christ. The Matrimonio mystico is an ultimate display and declaration of spiritual connection to Christ, basically stating someone is ‘married to their faith’. The majesty of this painting shows the profound importance of this declaration. Catherine, adorned in finest regalia and crown to signify her royal blood, presents her hand to the infant Christ, who rests in the Virgin Mary’s arms, surrounded by innumerable angels. In Carracci’s Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (circa 1585), he seems to swap majesty for intimacy and realism. In his scene, the Virgin Mary and infant Christ are depicted as relatively mundane figures with nothing separating them from the earthly realm. Their expressions are soft, and the use of light and dark is gentle, depicting this intimate holy moment opposed to the triumphant, populated painting by Veronese.

Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus (1601) and The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1602), and Carracci’s Christ Appearing to Saint Peter on the Appian Way (Domine, Quo Vadis?) (1601-2), show the moment followers and disciples of Christ are thrown into complete shock upon seeing him in the flesh – a feeling too emotionally and spiritually overwhelming that the witnesses are plunged into disbelief and incredulity. The idea of ‘incredulity’ was an innovative genre of religious painting in the sacred Baroque world and, as an explicit display of intense emotion, it most certainly delivered to the brief set out at Trent. Recalling the moment of revelation, Caravaggio cleverly adopts an unprecedented feat of storytelling in The Supper at Emmaus, which would have had such a profound impact on the faith of contemporaries. Having encountered the risen Christ on the road from Jerusalem to Emmaus, failing to recognise him, two disciples invite him to join them for supper at an inn, only when Christ blesses the bread were ‘their eyes opened, and they recognised him.’ Small details, such as the movement of the disciples, contributes to the feeling of astonishment. One is about to leap up from his chair in shock and the other raises his arm in sheer disbelief. Caravaggio has also made light a metaphor for recognition, for example, the impassive innkeeper’s face remains in the shadows suggesting he has not yet ‘seen the light’, or rather recognised Christ.

Paintings of Mary Magdalene ‘in Ecstasy’ also proliferated as displays of spiritual awakening. However, the line between depicting a moment of conversion versus a moment of sexual pleasure was extremely thin: most famously, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-52) came under the firing line as “overly physical” with the peak of ecstasy resembling the climax of sexual pleasure. But that is not to downplay Bernini’s work – it is, after all, a beautifully magnificent sculpture. Other artists, however, did manage to fall in step with what was and was not acceptable.

Caravaggio’s Magdalene Klain (post 1606) and Gentileschi’s Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (circa 1620-25) both show the saint in rapture in her solitude. Ecstasies and raptures were psycho-physical conditions at the peak of mystical activity – their use in sacred art makes the viewer want to experience what’s unfolding before their eyes rather than just look at it ‘from outside’. Both paintings portray Mary Magdalene physically and emotionally overcome in rapture, leaning back with her eyes closed and hands clenched together. In Caravaggio’s depiction, her mouth is open slightly which only adds to the uncontrollable nature of her spiritual awakening from her life of sin to a contemplative moral existence. The use of Mary Magdalene in ecstasy excited an emotional response from worshippers over the intensity and drama of spiritual awakening and religious conversion.

It is so easy to get completely lost in the world of the Baroque – paintings of the time were so intense and excited all senses and emotions. The 18th century travel writer Lady Anna Miller spoke of how she was thrown into a trembling and made very sick by the thought of Caravaggio’s gory scenes. This visceral reaction was desired by the Catholic Church to usher the faithful towards devotion, and it was the ‘Decree on Sacred Images’ that incited Baroque artists to answer the call. Religious subjects flourished and new artistic genres were innovated to create a multi-sensorial experience that enraptured and indoctrinated Catholics into fidelity and devotion to their faith.

A huge thank you to Molly for writing for us today, this is such a fascinating topic and not one we often explore on Just History Posts, so I hope you have all enjoyed reading it as much as I have.

Previous Blog Post: What Was A Court Jester In The Medieval Period?

You may like: Treasures of the Tudors: The Bacton Altar Cloth

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?