Surviving historical artefacts are so interesting to write about because there are so many strands of history they can illuminate for us. It could be teaching us about artwork and design popular in another time period, it can show us the skill of craftsmen from centuries or millennia ago, and in the case of the written word, one single item can carry an entire story of a human lifetime otherwise lost to history. The Liber Manualis was composed almost 1200 years ago, and is a unique item for its time. It tells us so much about politics, religion, education – and about a woman named Dhuoda. (Content note: mention of rape)

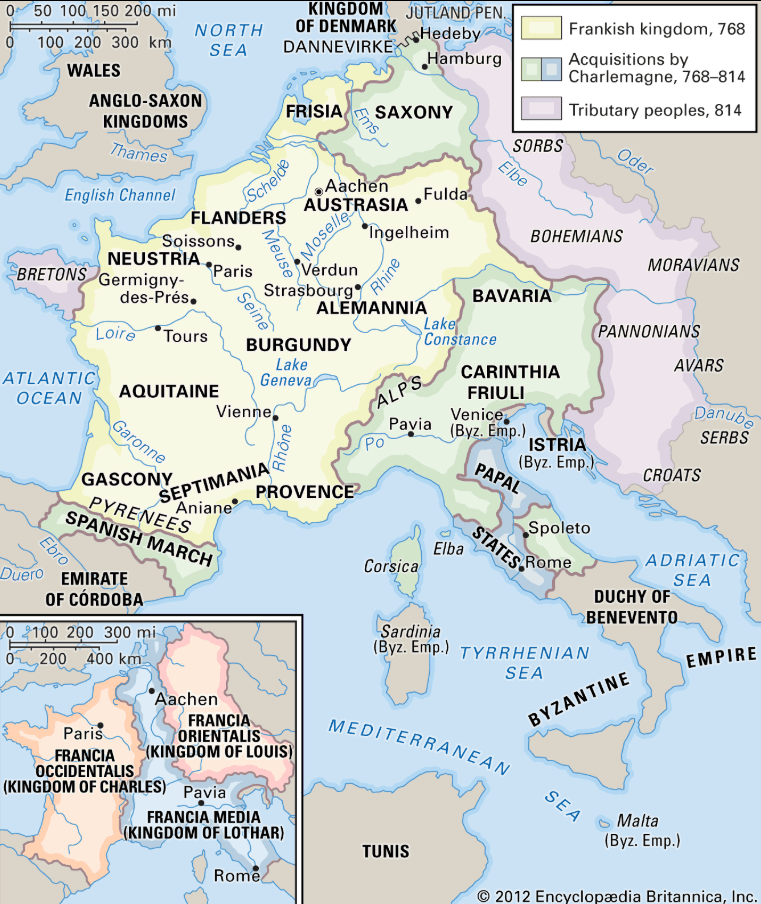

Dhuoda lived in the ninth century, in regions covering modern-day France and Spain. She lived during the height of the Carolingian dynasty, a Frankish family who took control of the area in the previous century, but made famous by Emperor Charlemagne (who you can learn about in another of our blog posts). We don’t know when she was born, but we do know that she married in 824 – seemingly her first marriage – and that she had children in 826 and 841, pointing to a birth date in the first decade of the century (around the year 805 being a common suggestion by historians).

We don’t know anything concrete about Dhuoda’s family, but they must have been very important nobles in the region for two reasons: her exemplary education, and her chosen husband. The first thing we do know about her life comes from her own hand, explaining that in June 824 she married a man named Bernard. Bernard was, himself, highly illustrious. His father was no less than a future saint – Saint William of Gellone – and his second cousin and godfather was Emperor Louis the Pious, son of the aforementioned Charlemagne. Bernard was also, either at the time of his marriage or within a year, Count of Barcelona and Margrave of Septimania, a region of modern-day southern France. The couple were married in a chapel in Aix, and it seems to have been a happy union at first.

At the time of their wedding, Bernard was around 24 years old, so the couple were similar in age and Bernard was by all accounts gallant, capable, and likely handsome too. Dhuoda recounted how she would travel with Bernard everywhere, through his territory in the dangerous Spanish Marches and beyond. After “the help of God”, the couple were blessed with their first child, a son named William after his grandfather, on the 29th November 826.

It wasn’t long, though, until Dhuoda’s family were flung into the dangerous politics of the era. Since Charlemagne’s death, Frankia had been in disarray, with Louis struggling to retain control over his three wilful sons. This was not the time for disunity, for there were plenty of rival dynasties on the frontiers of the empire. The edge of Bernard’s territory was constantly under threat from the Saracens of the Caliphate of Córdoba who had control of much of the Iberian Peninsula. In 827 they attacked Barcelona, and Bernard and his lands were in severe danger.

Louis attempted to send aid to Bernard in the form of his son, King Pepin of Aquitaine, and two other powerful counts, but Pepin was part of an anti-court party against his father and so the three did nothing to help. Louis then tried sending his oldest son, Lothair, but he too did not feel like doing much to help and delayed going. As such, Bernard was left with an almost impossible task in the face of a powerful enemy – and yet, he succeeded. In early 829, he finally repelled the invaders and was hailed a Frankish hero.

That summer, Louis rewarded Bernard by moving him, Dhuoda, and William to the palace of Aix and giving Bernard the office of chamberlain, the highest servant of the Emperor, and he was also given responsibility of mentoring the Emperor’s young son. Dhuoda was now, by proxy, an incredibly powerful and privileged duchess at the heart of the Carolingian court. But this joy was to be short-lived, for there were very swiftly rumours of an affair between Bernard and Louis’ wife, Empress Judith. Judith was Louis’ second wife and twenty years his junior, renowned for her beauty and intelligence. The chamberlain was expected to work very closely with the Empress, due to his role in managing the household. The rumours could have held substance, but were more likely designed to discredit two powerful political players: Bernard, who had just risen to a place of great prominence, and Judith who was disliked for her influence over the emperor and was accused of witchcraft.

Bernard was forced to flee the court the following year, with Louis and Judith facing an uprising from his sons. Louis was held captive by his son Pepin whilst Judith was sent to a convent and a bounty was placed on Bernard’s head. It is unclear what happened to Dhuoda and William during this time, though they almost certainly would have also fled to a place of safety. In early 831, Empress Judith stood trial and cleared her name as no-one in the assembly wanted to charge her of any crimes, and Bernard was also able to clear himself, but Louis was loathe to reinstate Bernard to his previous position. Bernard then, ironically, pledged his allegiance to Pepin and he and his family moved back to their lands in Septimania and the Spanish Marches.

The rest of the decade saw Bernard and Dhuoda constantly caught up in the in-fighting of the royal family, with Bernard losing and gaining his titles as Pepin lost and gained favour with his father. Amongst all this fighting, Bernard seems to have lost something of his youthful, chivalric charm that he had found defending Barcelona, and became more harsh and bitter. In 838, a complaint was lodge with the emperor regarding Bernard’s supposed tyranny. This seems to have tied in with increasing discord between Bernard and Dhuoda.

Emperor Louis died on the 20th June 840, and Dhuoda’s second child was born on the 22nd March 841, almost nine months to the day. At least one historian has suggested that this second baby – a son named Bernard – may have been born out of marital rape, looking at Dhuoda’s description of the event and the immediate aftermath. Whilst Dhuoda had written that her first son was born “with the help of God”, she instead recorded that Bernard was born “by the mercy of God”. She also explicitly mentions the death of Louis in the same line as Bernard’s birth, suggesting she very much considered the two events linked. Historian Allen Cabaniss thus proposed that Bernard raped Dhuoda in the days after Louis’ death whilst in a frantic mental state worrying about his future.

Whilst this could appear to be quite a leap from language inferences (Dhuoda’s choices of phrase could merely reflect firstly parental joy at their first child and heir, and perhaps a difficult second birth, considering her more advanced age at that time), there does appear to have been real discord between the couple at this time. Dhuoda had moved to Uzès to give birth, leaving William with his father in Aquitaine in service to King Pepin. Though this could just be explained by Dhuoda wanting to return to the comfort and security of the couple’s own territory to give birth, something more sinister was awaiting her. Bishop Elefantus of Uzès had been given orders by Bernard to collect his new child as soon as possible after their birth and bring them to him in Aquitaine. Thus, Dhuoda tells us, the child was traumatically taken from her before he had even been baptised. She did not even know the name given to the child.

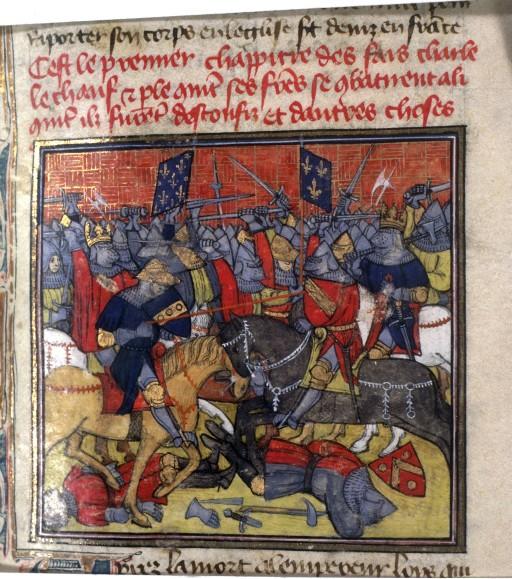

Clearly, then, Dhuoda’s retirement to Uzès was not an amicable agreement between the couple. Something had gone seriously wrong in their relationship. Dhuoda’s trauma was not yet complete, as her other child was soon to be put in danger. After the death of Louis, the kingdom had been split between his sons, but the sons did not agree on who received what. Charles, Louis’ only son with Judith, allied with his half-brother Louis against their brother Lothair, winning a key battle at Fontenoy in June 841. In the aftermath, Charles became King of West Francia, and thus would be overlord of Bernard and his family. Although Bernard was present at the battle, he did not send his troops to fight for either side, choosing to await the outcome. After Charles and Louis’ victory, Bernard decided to send his son William to the court of Charles in homage, with a promise that Bernard would help persuade Pepin to make peace with his brothers.

Dhuoda had now lost her newborn son, and her fourteen-year-old son was being used as a political pawn. As her son turned fifteen and Dhuoda was still alone, she decided to turn her fear and grief to productive matters. On 30th November 841, the day after William’s birthday, Dhuoda sat at a writing desk and picked up a pen, thus beginning her famous work, the Liber Manualis.

Dhuoda’s writing was intended to be an instruction manual for her son, to help him navigate the royal court and his life in general. As she could not provide her motherly guidance in person, she hoped that what she wrote down could be read by him time and again, also desiring that he would “teach them to your little brother whose name I do not know”. Consisting of over 70 chapters, the book was highly religious in nature, centring the Bible and Christian teachings as a guide to life. Dhuoda clearly knew the Bible extremely well, and was most fond of the Psalms which she quoted often. She cited many passages from the Bible from memory, as made clear by slight errors, variations or misattributions, and – perhaps surprisingly, given her strained relationship with Bernard – she emphasised throughout that William should place loyalty to his father above all other men.

Dhuoda chose to compose her book in Latin, exemplifying her excellent education. Although her Latin is not perfect, it reflects the level of skill of most other writers of the time, and she was able to create word plays and acrostics, demonstrating her talent with the language. Her level of education and her significant position in society placed her in a unique position to be able to compose her book: the Liber Manualis is the only surviving book written by a woman in the Carolingian period. Whilst this does of course come in part from the ravages of time, it does suggest that there were few women undertaking such a task at all. She also mentioned using numerous texts to help her compose her own writing, suggesting she had access to a good library.

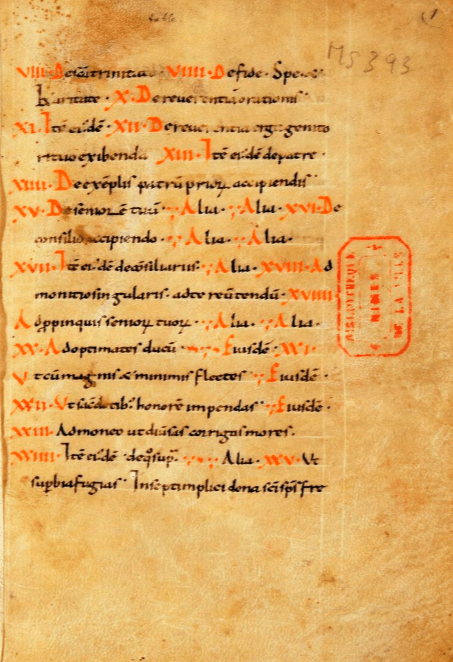

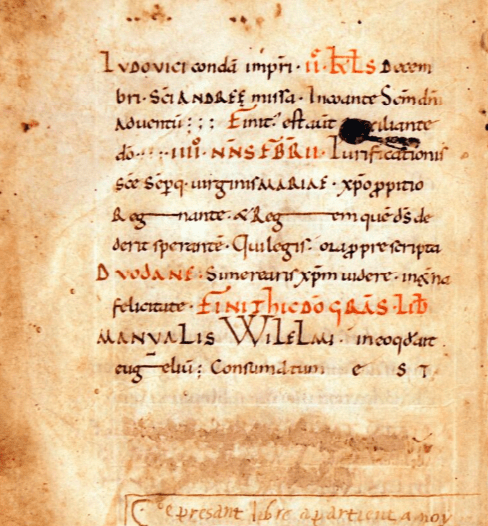

Fragments of Dhuoda’s book survive in Nîmes, one of the cities that were part of Septimania not far from Uzès, and as the manuscript dates from the ninth or tenth century this could very well be her original book. There is a fourteenth-century copy in Barcelona which contain a few extra passages than other versions, and the text also survives in a seventeenth-century copy held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The book has been considered invaluable to historians for its insight into how Carolingian nobles taught their children, their knowledge and relation to religion, and the education of women. But it is also of vital importance in learning about Dhuoda as a person. To hear of her own life in her own words is exceedingly rare for much of the medieval period, not just the Carolingian, and it is more-or-less the only source we have about her life. Dhuoda wrote for fourteen months, finally putting down her pen on the 2nd February 843. After this point, we know nothing else of her. No record survives in history apart from her book.

From her own writing, it appears she had not reconciled with her husband, and she had been forced to take out numerous loans to survive and continue the defence of their lands. She begged William to repay her debts if she died before she could repay them herself – she mentions in Book 10 that “the cruel sting of sickness consumes my whole frame,/ I’ve assembled this quickly for you and your brother,/ since I know I can’t live till that hoped-for time [when he is older and they are reunited]”. Dhuoda’s despondent outlook was not without cause. In August, Empress Judith died after a long sickness of her own, and Charles, unrestrained by his mother, took the opportunity to bring Pepin to heel at last. He launched a significant campaign into Aquitaine, and by the end of the year Bernard was captured. He was executed for treason in early 844.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Dhuoda’s high hopes for her son were not to come to fruition. Disinherited by his father’s execution, the seventeen-year-old William joined Pepin’s rebellion. Though he was later successful in receiving his father’s lands and titles in Barcelona, the wars between Pepin and Charles eventually caught up to him. He was killed in Barcelona in 850 by supporters of Charles. It has been proposed that he may have died still in possession of Dhuoda’s book, with the fourteenth-century copy held in Barcelona being copied out at that time from the original manuscript still in the city.

Dhuoda’s second son, whose name we can only hope she eventually learned, fared somewhat better than his father and brother. As he entered maturity, he was granted his ancestral lands as Bernard II of Septimania. He gained more titles later in life, becoming Count of Autun in central-eastern France, and receiving control of the county of Mâcon, Autun’s neighbour. He went on to marry Ermengard, countess of Auvergne in her own right, and they had four known children together, including the future Duke William I of Aquitaine.

There is one glimmer that Dhuoda may have outlived her husband and potentially remarried: a chronicler, Ademar of Chabannes, wrote almost two centuries later that Dhuoda’s son William had a sister, who married the count of Poitiers and Angoulême. Some have suggested that if this daughter did exist, she was born to Dhuoda and Bernard in 844 or 845, but this seems unlikely. She certainly doesn’t seem to have been born in between William and Bernard, as Dhuoda makes no mention of another child in her Liber, and as discussed, the book certainly does not suggest a reunion between Dhuoda and Bernard by its completion. Considering Bernard was then captured and executed less than a year later, it seems unlikely the couple had reunited before then. She could have been an illegitimate daughter of Bernard, but whether an illegitimate child would have made such a good marriage when her father was dead is questionable. This daughter may not have existed, Chabannes having incorrect information writing so much further in the future, or perhaps Dhuoda found another husband after Bernard’s death. If so, we may hope she had a slightly happier union.

Though Dhuoda lived more than a millennium ago, her influence remains today because of her decision to put her life and knowledge on paper. In recent decades, after translations of her work became more widely available, scholarly interest in her has rocketed, with many books and articles about her. She has exerted particular influence in her husband’s city of Barcelona, where a street is named in her honour, as is the Duoda Women’s Research Centre at the University of Barcelona. Whether she lived long enough to see the fate of her family, or if she died in poverty and obscurity is not known – perhaps one day further research may uncover something, or perhaps her fate is lost to time. What is known, however, is that she reclaimed some power and autonomy by putting her thoughts and feelings in her own words, words which have survived 1,200 years to us today, privileged enough to read them.

Previous Blog Post: Just History Posts in 2025

Previous in Historical Objects: The Bees of Childeric I

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

Dhuoda: Handbook for her Warrior Son: Liber Manualis, Marcelle Thiebaux

The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters, Allen Cabaniss

One response to “Historical Objects: Duchess Dhuoda and the Liber Manualis”

[…] Previous Blog Post: Historical Objects: Duchess Dhuoda and the Liber Manualis […]

LikeLike